As we turn the corner from summer to fall, we wanted to share updates on several of our ongoing field studies as well as research projects planned during polar bear season in Churchill, Canada this fall—including some new studies related to polar bear tourism.

Photo: Kt Miller / Polar Bears International

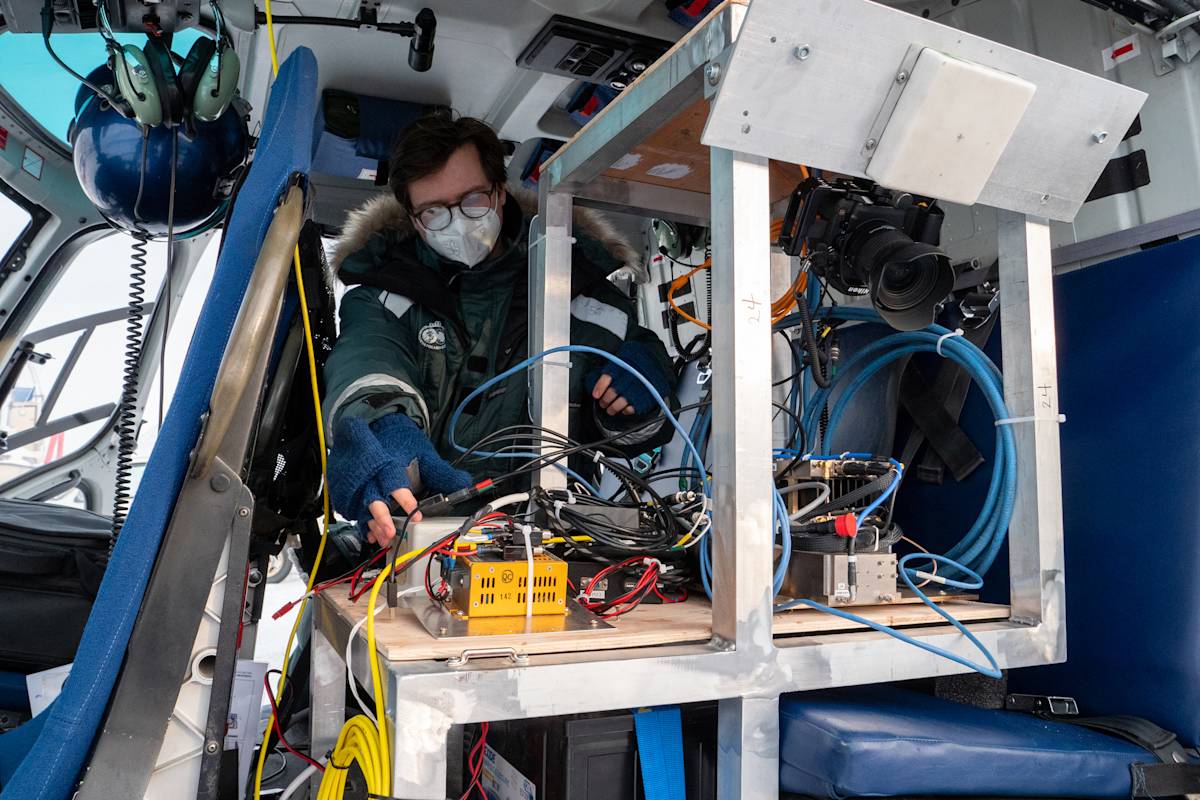

Jeff Stacey, a graduate student from Simon Fraser University, prepares the SAR unit for testing in the helicopter.

Updates on Field Research

By Barbara Nielsen, Senior Director of Communications

MINS

12 Oct 2022

Den-detection study

BJ Kirschhoffer, our director of field operations, reports promising results related to the den-detection study conducted in Svalbard, Norway earlier this year. Our test flight to find dens under the snow through the use of synthetic aperture radar, or SAR, successfully pinpointed a polar bear in a known den. This is important because being able to find and map active dens will aid managers in protecting moms and cubs.

“After the data from our test was processed, using tools created by our partners at Simon Fraser University, we were able to see an image that correlated to a satellite-collared female polar bear in an active den,” Kirschhoffer said. “Needless to say, this was exciting news that encourages us to keep pushing forward with this technology.”

“Burr on Fur” tracking devices

Our partners at the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources deployed four Burr on Fur tracking tags on adult male polar bears during field work this fall, helping us test the effectiveness of these small, stick-on tracking devices. Geoff York, our senior director of conservation, said the team deployed three crimp-style tags and one tri-brush tag.

Three of the prototypes were made from upcycled whitewater raft material. Not only is it more durable than what we had before, it’s also flexible, thinner, lighter, and better able to withstand cold.

In addition to testing the Burr on Fur tags on wild polar bears, we continue to work with our Arctic Ambassador Center network to test them on zoo bears, with the Toronto Zoo our latest partner in this effort. In addition, we are moving forward with testing the tags on rehabilitated and released black bears, again in partnership with the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources.

Photo: Kieran McIver / Polar Bears International

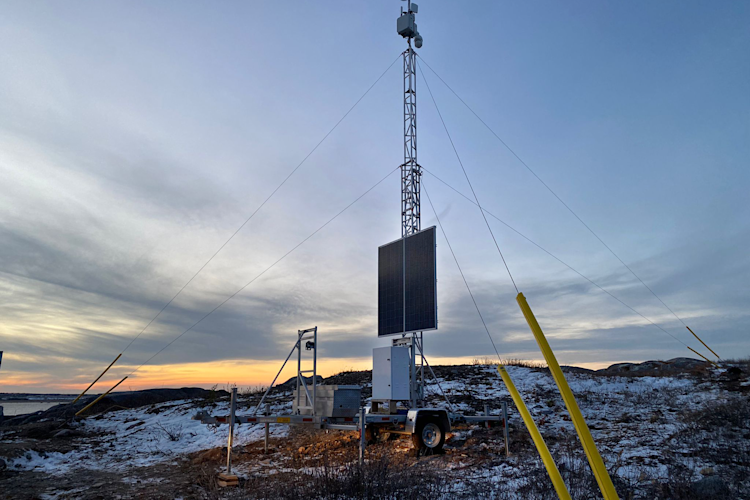

Polar Bears International's new mobile radar tower.

“Detect and Protect” radar

Being able to detect an approaching polar bear before it enters a community will go a long way in helping people and polar bears to coexist. Our staff scientists continue to work on fine-tuning radar technology for use in detecting polar bears—a novel application they refer to as “bear-dar.”

This summer, the team pioneered the use of a mobile tower that allows them to quickly and easily reposition one of the systems they’re testing: the Spotter Global, a medium-priced radar with a medium range. During bear season, they plan to move it near Cape Merry , a popular thoroughfare for polar bears. The data gathered during bear season will help fine-tune the system’s AI with a goal of identifying polar bears with at least 95 percent accuracy.

In addition to Spotter Global, the team will test two other promising systems during this year’s bear season. The first, from Hensoldt, includes both daylight and night vision radar. The cameras for each have already been mounted on the roof of Churchill’s waste facility, ready to gather imagery of approaching bears. The team will use this data to test their AI models, hoping that what we’ve learned from the Spotter Global can be applied to the Hensoldt images. The Hensoldt radar is the most expensive of the three types being tested and also has the longest range.

And finally, the team will be testing a model developed by a professor and students at Brigham Young University. This system is the least expensive and also has the closest range. It will be mounted on Tundra Buggy One, giving it the advantage of being easily put in front of bears as the buggy roams across the tundra. The beauty of this system is that it’s a portable, self-contained, plug-and-play unit—just one box that connects to the internet. It uses a combination of visual and radar data to build its AI model.

“Each tool has its own range, making some better for communities, others for camps or work stations, ” says Kirschhoffer. “Ideally, we can train them to identify polar bears with a high degree of certainty. We’ve already established that the radar sees everything. Being able to see is not the problem. Filtering out the noise is the problem.”

Tourism impact studies

New this fall is a project that will lay the groundwork for a study to examine effective viewing distances for polar bear tourism, starting with the launch of a literature review and gap analysis led by Kamryn Dehn, a graduate student at the University of Miami.

In addition, we’ll be working with Frontiers North to see if machine learning can be used to quantify the number of days that Churchill can see northern lights. The plan is to take imagery from the explore.org Northern Lights cams, then put it through an algorithm to count the number of nights that northern lights can be seen from Churchill—all part of our outreach to help people fall in love with the Arctic.

Be sure to follow our social media this fall for news and updates from Churchill during the annual gathering of polar bears. Every fall, polar bears congregate on the shores of Hudson Bay near Churchill to wait for the sea ice to return—an icy platform that they rely on to hunt their seal prey.