Activity 1B: Explore

Photo: Craig Taylor/Polar Bears International

Polar Bear Adaptations

Read the following text and watch the included videos. Some of this will be review – but please use this as a confirmation of the knowledge you have about polar bear adaptations. Polar bears are highly specialized and built for life on the sea ice. This is key in understanding why they are so vulnerable to changes in their environment.

The Arctic sea ice ecosystem

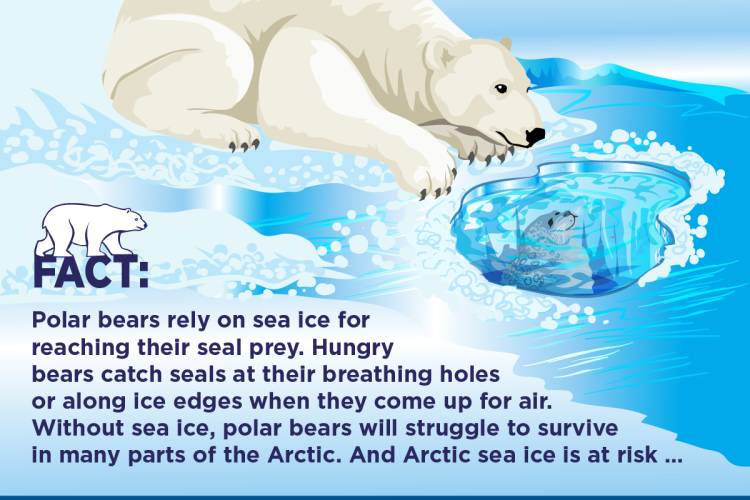

The Arctic food web is fragile and made up of fewer species than ecosystems in other regions of the world. Sea ice is critical for sustaining this marine ecosystem, from the top of the food chain as well as from the bottom (see graphic below)—in fact, a recent study found that at least in some areas more than 70% of the carbon making up the polar bears’ diet can be traced back to the algae growing underneath the sea ice (source). Polar bears are also dependent on the sea ice as a platform from which to hunt their main prey, the ringed seal and the bearded seal.

Now let's start at the beginning....polar bear evolution

Evidence suggests that precursors to modern polar bears first appeared up to four or five million years ago. However, estimates of when the split happened vary widely, as even after brown bears and polar bears separated into two distinct species, there were periods when they came into contact again and bred with each other. Ultimately though, the polar bear's ancestors diverged from brown bears and underwent a series of evolutionary changes in order to survive in the harsh conditions of the Arctic – adapting to a life of hunting seals and surviving extreme cold.

Genome studies further reveal little genetic diversity in today's polar bears, suggesting bottleneck periods, probably during warm periods, when their numbers were severely reduced. (A genetic bottleneck occurs when a population is greatly reduced in size. The bottleneck limits the genetic diversity of the species because only a small part of the original population survives). Similar bottlenecks are likely to appear again, as indicated by a recent study which found a sea ice related significant reduction in geneflow between polar bears in different areas of the Svalbard archipelago.

Guiding question: What does this mean in the face of the current Arctic warming now taking place?

First, the longer evolutionary period shows that polar bears won't be able to adapt to changing sea ice conditions within a mere one hundred years.

Second, although the longer time frame means that polar bears survived previous warm periods, the temperatures reached in the Arctic if we continue on our present warming course will be unlike anything polar bears have survived before.

Physical adaptations

Polar bears have developed special adaptations to survive in their harsh environment.

Skin. Polar bears have black skin under which there is a layer of fat that can measure 4.5 inches (11.5 centimeters) thick. This fat acts as insulation as well as energy storage.

Fur. Polar bears' fur consists of a dense, insulating undercoat topped by guard hairs of various lengths. It is not actually white—it just looks that way. Each hair shaft is pigment-free and transparent with a mostly hollow core that scatters and reflects visible light. Polar bears look whitest when they are clean and in sunlight, especially just after the molt period, which usually begins in spring and is complete by late summer.

On land (or on top of the sea ice) the polar bear's thick fur coat—not its fat—prevents nearly any heat loss. In fact, adult males tend to quickly overheat when they run.

In the water, polar bears rely on their fat layer to keep warm: wet fur is a poor insulator. This is why mother bears are so reluctant to swim with young cubs in the spring: the cubs don't have enough fat. As long as they don't have to go into water, dry fur keeps little cubs warm at very cold spring temperatures, down to at least -30°F/-34°C.

Fiber Optic Fur? Scientists used to think that polar bears' hollow hairs acted like fiber optic tubes and conducted light to their black skin. However, a 1988 study In 1988 proved this false: the experiment showed that a one-fifth inch strand of polar bear hair conducted less than a thousandth of a percent of applied ultraviolet light.

Paws. Polar bear paws are perfect for roaming the Arctic. Paws measure up to 12 inches across (31 centimeters) and help distribute weight when treading on thin ice. When ice is very thin, polar bears extend their legs far apart and lower their bodies to distribute their weight even more. They are expert at placing each paw precisely and quietly when stalking seals. When swimming, forepaws act like large paddles and hind paws serve as rudders.

Black footpads on the bottom of each paw are covered by small, soft bumps known as papillae. Papillae grip the ice and keep the bears from slipping. Tufts of fur between their toes and footpads may help with purchase as well, as can their claws. Polar bears typically move slowly and methodically and like to walk on patches of snow better than slippery ice.

Claws. Polar bear claws are thick and curved, sharp and strong. Each can measure more than two inches (5.1 centimeters) long. Bears use their claws to catch and hold prey—and to provide traction on the ice.

Ears and Tails. Polar bears' ears are small and round and their tails are short and compact. This helps bears conserve heat.

The bear necessities...

Polar bear senses and communication

Polar bears use a combination of body language, vocalization, and scent to communicate.

Head wagging from side to side often occurs when polar bears want to play. Adult bears initiate play—which is actually ritualized fighting or mock battling—by standing on their hind legs, chin lowered to their chests, and front paws hanging by their sides

Nose-to-nose greetings are the way a bear asks another bear for something, such as food. The guest bear will approach slowly, circle around a carcass, and then meekly touch the other bear's nose. Bears who use proper manners are often allowed to share a kill.

Chuffing sounds are a response to stress, often heard when a mother bear is worried for her cubs' safety. Mother bears scold cubs with a low growl or soft cuff. When a male approaches a female with cubs, she rushes toward him with her head lowered.

Hissing and snorting and a lowered head all signify aggression. Loud roars or growls communicate anger. Deep growls are warnings, perhaps in defense of a food source. Attacking polar bears charge forward with heads down and ears laid back. Submissive polar bears always move downwind of dominant bears. Polar bear cubs make a variety of sounds from hums to groans to cries when communicating with their mothers. You can listen to some of these vocalizations in this blog post.

Scent communication between polar bears plays an important role, particularly during mating season. In the video above, Dr. Megan Owen details the findings of a study on how scent glands between the toes on polar bear foot pads helps them convey information on sex and reproductive status.

Stay tuned for more information on how zoo polar bears inform the conservation of the species in the wild, in Activity Four: Working with your AAC Team.

Guiding Questions: Which of these behaviors have you witnessed from the bears at your institution? Are there ever any opportunities in your communications to relate individual behaviors to species specific behavior in the wild? Show of hands...Are there opportunities at your institution for marketing/communications teams and animal care teams to work together when communicating about the animals in your care? For example, do you work together on FB live events, keeper blogs, videos, media interviews. etc. Share some examples on collaborative efforts in Discord!

One of the goals of the PBI Climate Alliance is to build capacity within your Arctic Ambassador Center (AAC) teams and help facilitate more working relationships across departments in each institution. We should all be working toward the common goal as an AAC – to preserve a future for polar bears across the Arctic.

Mating and denning

To start, Watch our Denning is Essential video on the study that found that current den-detection surveys, conducted by the oil and gas industry to locate and hence protect polar bear dens, have been missing over half of known dens. The high failure rate has implications for policy decisions in sensitive denning areas like the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. Follow-up by viewing our chief scientist’s testimony to Congress about the risks to moms and cubs from proposed drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

Polar bear mating takes place on the ice in March through May, but the fertile ova do not implant until the following fall. This is called delayed implantation. Females will enter the dens in November and will give birth to (on average) two cubs about two months after they enter the maternity den, usually by early January.

Newborns are 12 to 14 inches long (30–35 cm) and weigh little more than one pound (0.5 kg). Cubs grow rapidly on their mother's rich milk.

The family remains in the den until March or early April. During her entire time in the den – four to eight months – the mother bear doesn't eat or drink. When she finally emerges with her cubs, she leads them to the sea ice so she can break her long fast by hunting seals and ringed seal pups (spring is ringed seal pupping season, during which the bears feast on the seal pups they catch by breaking through the snow roof of the seals' birth lair out on the sea ice). However, if she has any energy depots still left after the time in the den, the mother may opt to stay around the den site for a few days to let the cubs get used to moving in snow before the family head out to the ice.

For at least 20 months, cubs drink their mother's milk and depend on her for survival, though the mother may produce less fat-rich milk, or stop lactating earlier if her body condition drops too low. Her success at hunting is critical for her own needs and for teaching cubs to find food for themselves. The cubs will stay with their mother for 2-2.5 years.

Additional Reading

Please view this Live Chat to learn more about how we study moms and cubs!

Denning occurs either on sea ice or on land. Watch the following two videos about denning in Hudson Bay, Canada and in Svalbard, Norway.

Guiding question: How is climate change impacting polar bear denning and reproduction?

Photo: Kt Miller / Polar Bears International

Finished?

Continue on to Activity 1C – Reflect.