Photo: Alexandra Langwieder / McGill University

Southern Hudson Bay Polar Bears

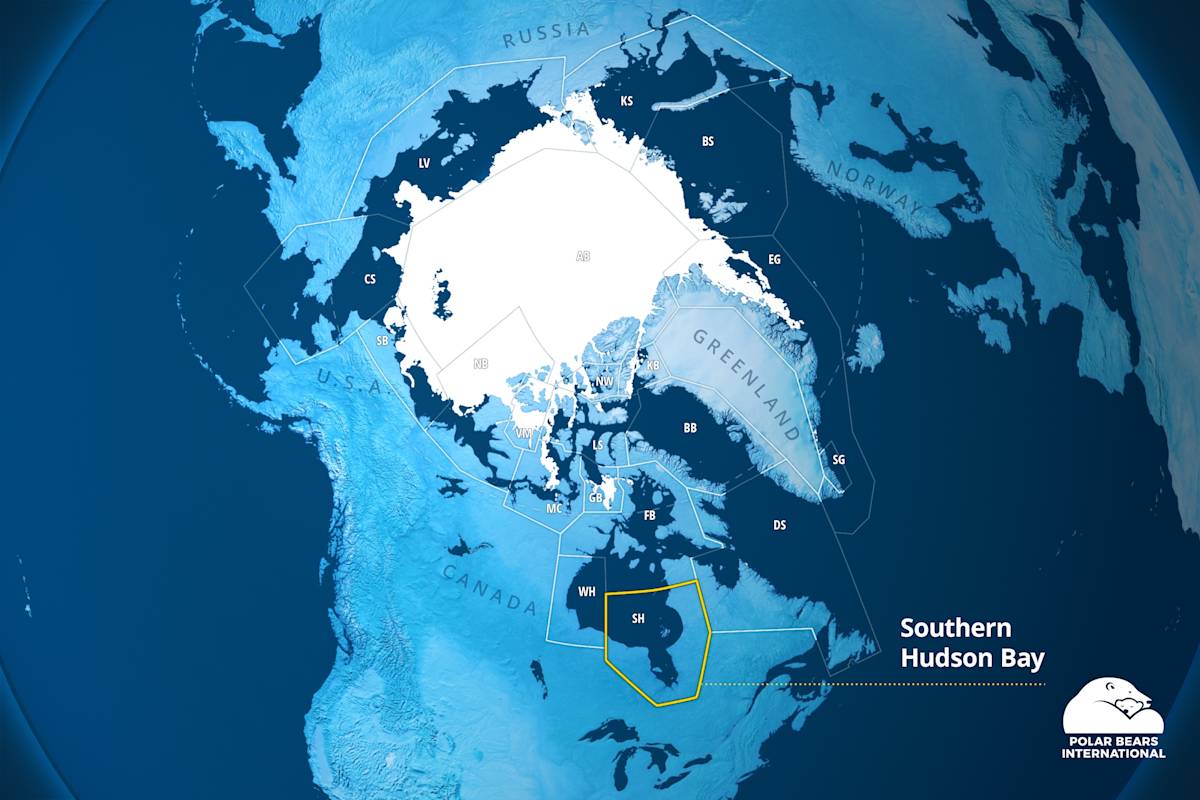

The polar bears of Western Hudson Bay are probably the most famous in the world, thanks largely to their proximity to the town of Churchill. But they are not the only polar bears in Hudson Bay. To the east and south is the Southern Hudson Bay population, which shares many similarities to—but also some significant differences from—its neighbor.

Location and Boundaries

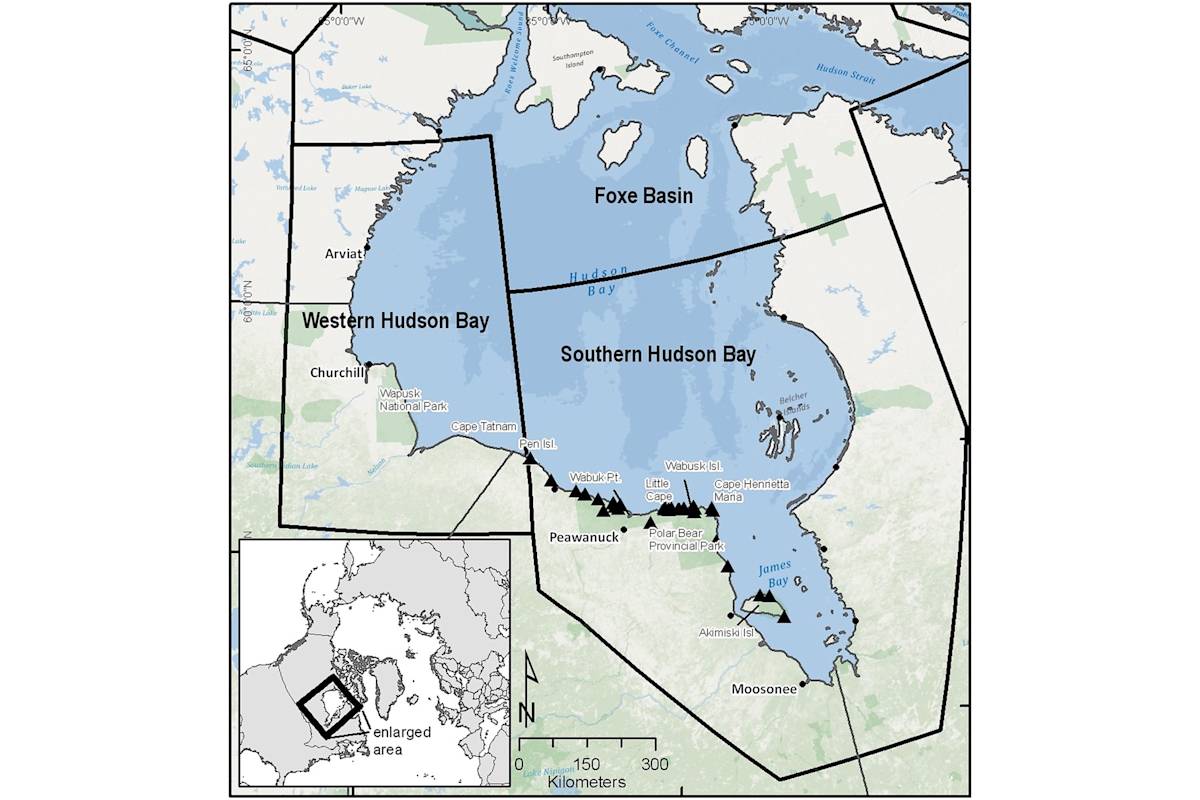

The polar bears of Southern Hudson Bay live farther south year-round than any other polar bears in the world. The population's range encompasses the eastern and southern parts of Hudson Bay as well as James Bay, which extends to the south. It includes most of the coast of Ontario, much of the western coast of Quebec, and multiple islands in both Hudson Bay and James Bay.

Photo: Middel, K. & Obbard, M, 2024

Location of the Southern Hudson Bay and Western Hudson Bay polar bear subpopulations.

Summer Fasting

Like Western Hudson Bay, Southern Hudson Bay is in the seasonal sea ice ecoregion, in which sea ice all but disappears during the summer months. Historically, Southern Hudson Bay has been ice free from late July or early August into late November; more recently, while ice may still persist into August, the bay rarely refreezes until mid-to-late December. In the most southerly part of the range, in James Bay, ice can break up earlier in the spring and generally refreezes later than the rest of the population area.

Because the sea ice in Hudson Bay travels counterclockwise, bears in this population tend to stay on the ice longer and until later in the season than their neighbors to the west, waiting until the currents deposit them and the slowly-melting ice floes on which they have been living at the bottom of the bay. But, like those neighbors, they come ashore during the summer months and wait for the ice to return.

However, the habitat where they spend that time is very different. In Western Hudson Bay, it is mostly tundra; in Southern Hudson Bay, although there is substantial tundra along the coast, the landscape is predominantly boreal forest—the only part of polar bears’ range in which some individual bears spend a lot of time in a forest ecosystem.

Photo: Alexandra Langwieder / McGill University

A Challenge to Study

That forest habitat can present a challenge for scientists attempting to study the Southern Hudson Bay population.

Researchers count polar bears from the air; when they want to study individual bears more closely, they fire tranquilizer darts that enable them to weigh, measure, and closely study bears after they fall asleep. However, the dense tree cover in some parts of this ecosystem, atypical of polar bear habitats, can increase the difficulty of both observing bears and being able to land to examine them more closely.

Also adding to the challenge: whereas the Western Hudson Bay population area includes the town of Churchill, Manitoba, there are no communities of similar size or connectivity in the Southern Hudson Bay region, making the logistical difficulties of arranging research expeditions and even reaching the area all the more difficult.

Threats to Southern Hudson Bay Polar Bears

Photo: Mitch Bowmile

Climate Change

There are some indications that the polar bears of Southern Hudson Bay may be dealing slightly better with the impacts of climate change than their neighbors in Western Hudson Bay. Although the population has seen significant decreases in body size, condition, and weight, the area continues to see apparently more robust reproduction and higher numbers of cubs than in Western Hudson Bay, possibly because the bears are able to stay on the ice for a little longer each year, eating seals and building up energy. Indeed, a recent study found that Southern Hudson Bay bears had roughly 10 extra days per year on the sea ice during the study period.

Photo: Alexandra Langwieder / McGill University

Harvest

Southern Hudson Bay is likely recovering from an unusually high harvest event in 2010, both in total harvest and the percentage that was female. That singular episode could partially explain both the past decline, as abundance was reduced along with depressed reproductive output, and play a role in this potential increase, as females previously too young to reproduce are finally reaching maturity and seeing success.

Outlook for the Southern Hudson Bay Population

Recent population estimates, on the surface, appear encouraging. After some apparent declines in the early part of the century, numbers appeared to stabilize temporarily, and the most recent survey, in 2021, produced an estimate of just over 1,000 bears, an increase on the 2016 estimate of 780 (but within the margin of error for both studies). That increase came as the Western Hudson Bay population fell from an estimated 949 to 618. However, those figures may not tell the whole story: Scientists believe that we may be witnessing an exchange of bears between the two populations, with bears from Western Hudson Bay lingering on the dwindling ice as it drifts toward Southern Hudson Bay and staying in the more southerly population after they come ashore.

A 2024 study supported by PBI finds thatSouthern Hudson Bay bears have access to seals for about 10 days longer in summer than Western Hudson Bay bears. This might explain the greater reproductive success noted in this population, with a higher proportion of cubs and yearlings.

The overall prognosis for all the polar bears in Hudson Bay is, however, grim. As warming continues, it is Southern Hudson Bay that will see the most extreme and rapid change. In 2024, these bears were onshore and fasting for a record-breaking 197 days.

A 2024 study concluded that, should the world warm by 2ºC or more, Southern Hudson Bay would be sea ice-free for between 174 and 182 days a year, which would impair reproduction and strain survival, leaving the population at risk of disappearing as early as the 2030s.

Without action to halt climate change, all the bears in Hudson Bay, in both populations, are at risk.

Photo: Alexandra Langwieder / McGill University

A mother polar bear and her cub walk near the hair snare sampling station that was part of a community-based research project near James Bay.

What Polar Bears International Is Doing

PBI is working with multiple partners in the region to support scientific research into, and understanding of and coexistence with, the bears of Southern Hudson Bay.

PBI helps to support population counts of the Southern Hudson Bay bears so we can understand how the bears are faring.

PBI has been supporting the efforts of Cree communities in southern Hudson Bay to coexist with polar bears, working in partnership with the governments of Ontario and Canada, and with York University.

PBI is helping to fund community-based research, using community-approved methods, in James Bay, at the southern end of Hudson Bay.

PBI supported the first paper to describe the movements of Southern Hudson Bay polar bears.