Photo: Kt Miller / Polar Bears International

Indigenous Knowledge in Churchill

A storywork research project explores the distant past, past, present, and future visions of human-polar bear coexistence with Swampy Cree, Sayisi Dene, Métis, and Caribou Inuit Elders and Knowledge Keepers.

Polar bears and people have shared northern coastlines for time immemorial, yet concerns about polar bears coming into communities is increasing. As the Arctic warms and the sea ice retreats, polar bears are spending more time onshore, making coexistence strategies between people and polar bears increasingly important. This study, published in Nature Communications Earth & Environment, used community-based participatory research, coproduction of knowledge, storytelling, and the “hands back, hands forward” methodology (which links historical knowledge with future solutions) to document Indigenous knowledge of human–polar bear coexistence in Churchill, Manitoba, Canada.

One goal of this research project was to provide to the community of Churchill with an approachable, engaging, and artistic way to interact with the research results through a podcast storytelling format—in the words of the participants themselves.

The podcasts below share stories, with permission, from the participants from a distant past, past, present, and future perspective.

Photo: © Aaron Janzen / Oceans North

Researchers

The study was conducted by Kt Miller in collaboration with Polar Bears International and Environment and Climate Change Canada as part of her master’s thesis at Royal Roads University. Her co-researchers were Georgina Berg, a Cree Elder and lifelong resident of Churchill, Manitoba; the Indigenous Knowledge Keepers of Churchill; and Dr. Michael Lickers, Nickia McIvor, and Dr. Dominique A. Henri.

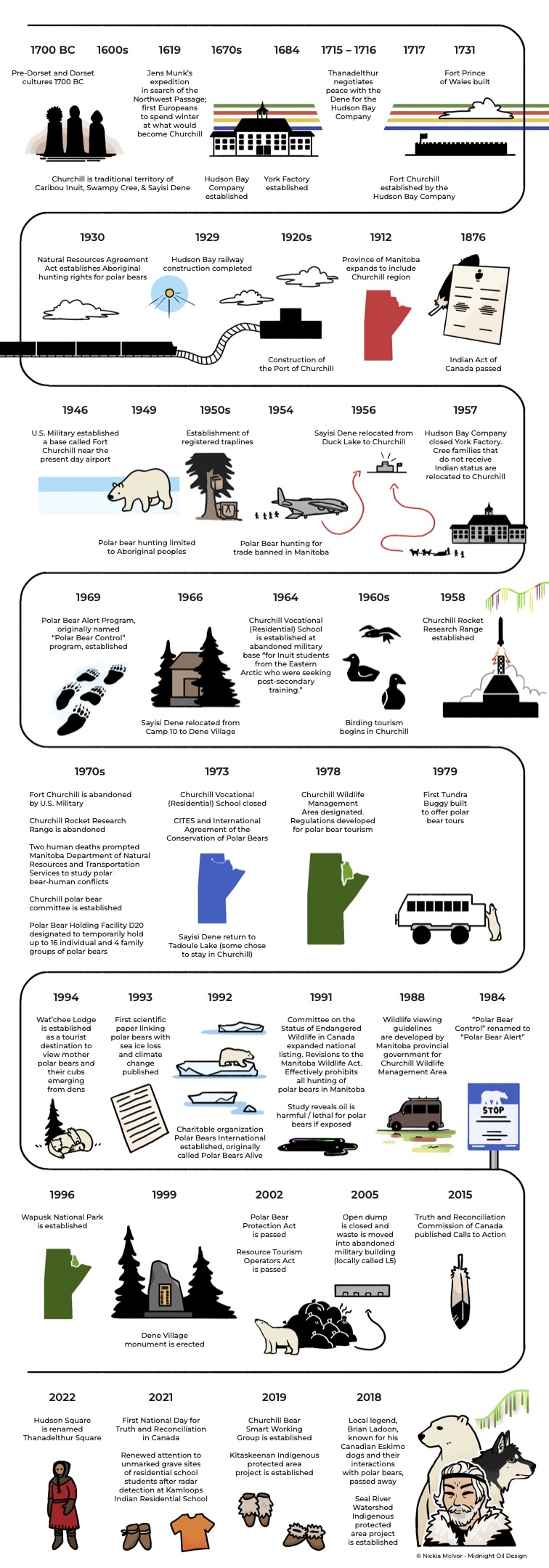

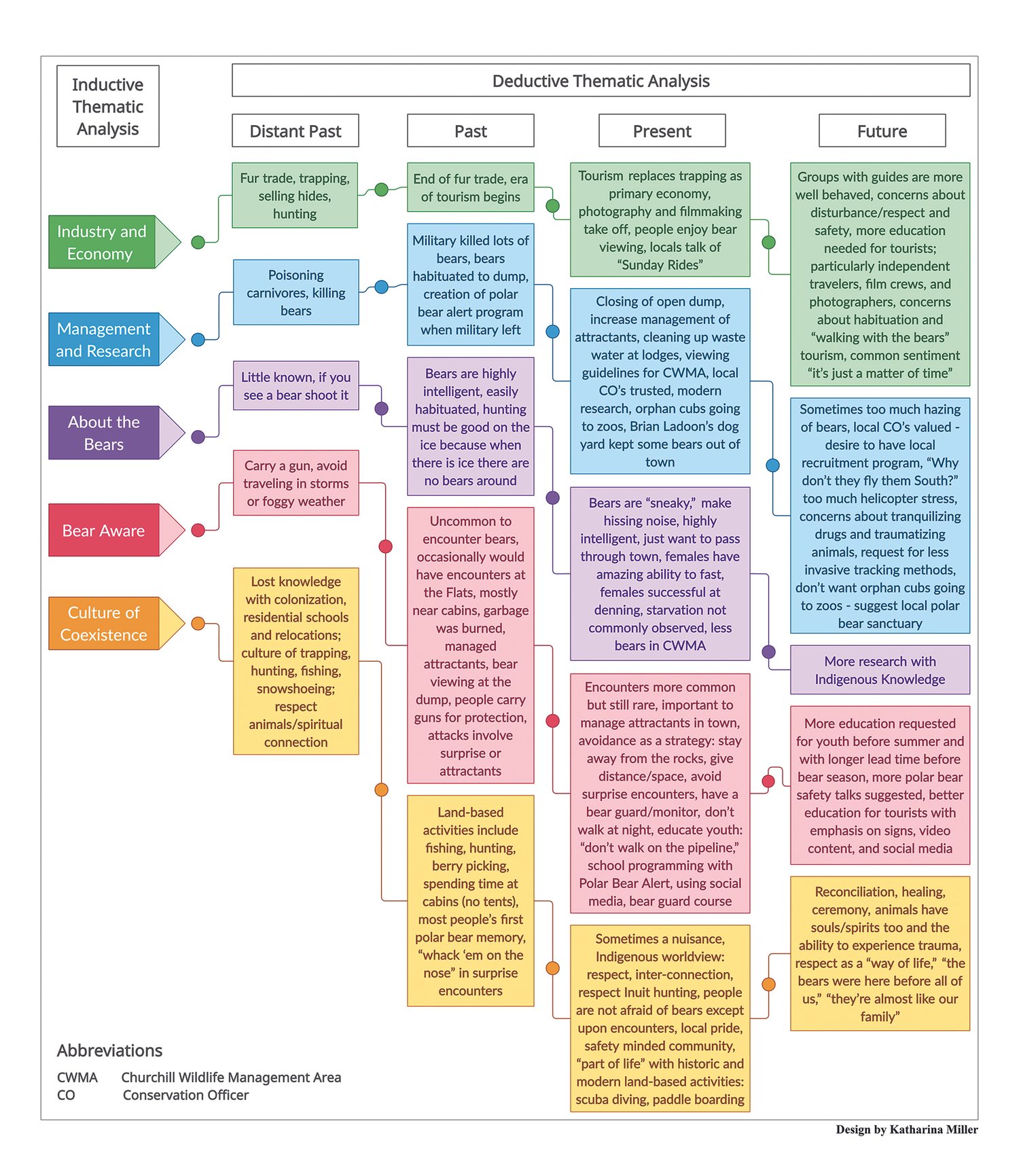

Timeline

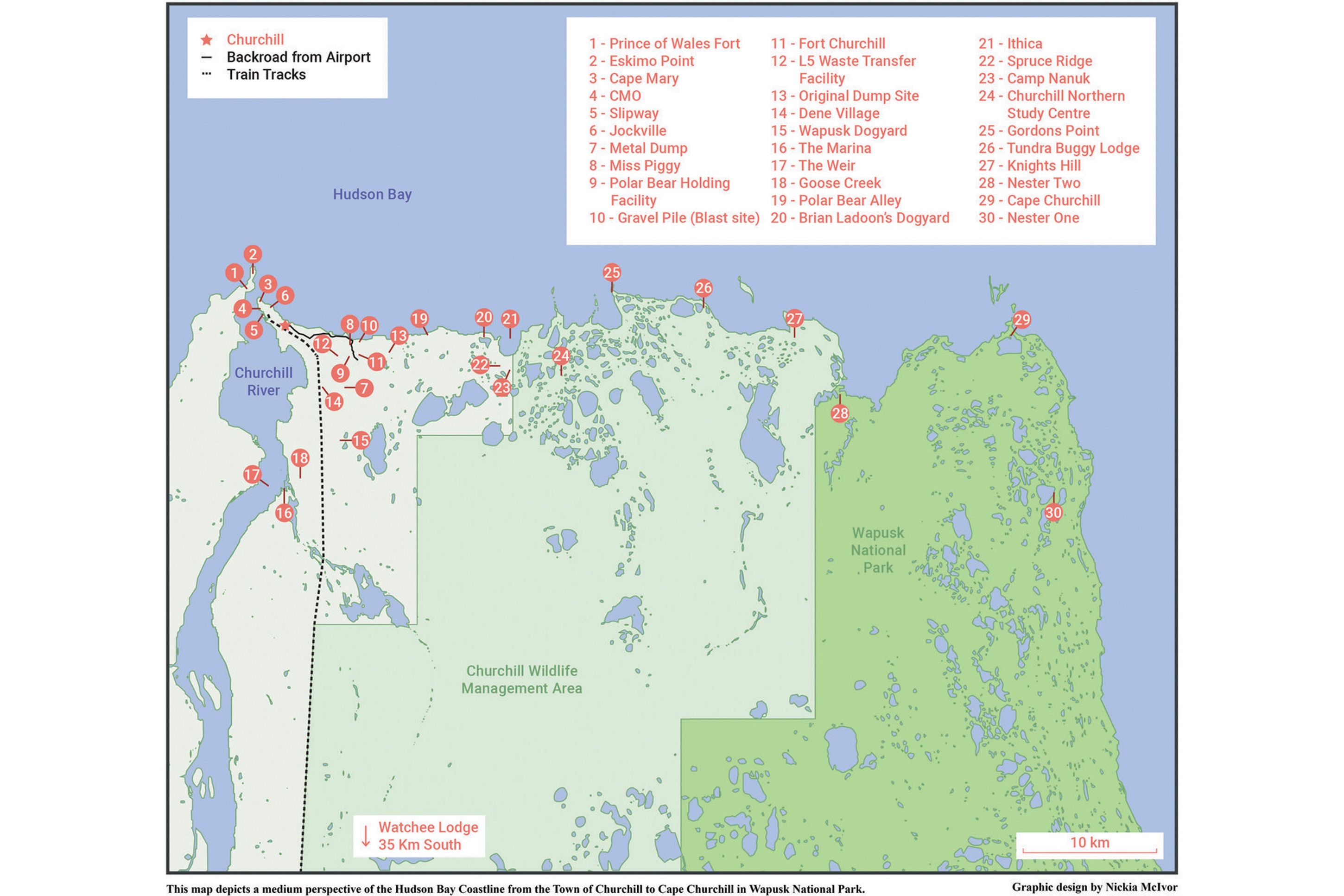

A timeline of significant Indigenous events and significant events related to polar bears in Churchill, Manitoba, Canada. Co-created and designed by research participant © Nickia McIver.

“I think this storytelling is what our people used to use before, and I think there’s a lot of healing in it.”

— Cree Elder

Episode One

In the distant past—defined by this project as intergenerational knowledge prior to 1957, when the Cree and Dene were relocated to present-day Churchill—the fur trade was the primary economy on the shores of Hudson Bay. Polar bears were not often seen, and when spotted they were killed, with the meat primarily used for dog food and the hides sold to a trading post. Much intergenerational knowledge was lost when people were relocated to Churchill, where it was, to quote an Elder, “all about a new life.”

Episode Two

From 1957–2005, defined by this project as the past, the era of the fur trade came to an end and a new era of tourism began. Participants recalled that the military shot a lot of polar bears and kept the hides, hanging them on their walls or using them as rugs. They also recalled seeing large numbers of bears eating burning garbage at the open dump. Concurrently, tourism began and polar bears started to become more valuable alive than dead. In 2005, the open dump was closed and moved inside an old military warehouse (L5). Once the military left and the open dump closed, people started to see a lot more polar bears coming through town. Most participants’ first memory of a polar bear occurred during this time period, outside of a cabin at the Flats (on the outskirts of Churchill), from a house in town, or at the dump. Even though all participants had encountered polar bears many times, they did not speak of polar bears fearfully, but rather with respect and sometimes even humor and joy.

Episode Three

In the present, defined as 2005–2022 for this study, most people’s knowledge of polar bears came through tourism and Land-based activities. Of research participants, 83% were connected to tourism through their job in some way. Unlike their parents, children are now told not to play in the rocks or walk along the gas pipeline on the outskirts of Churchill. Many parents now drive their kids around town, especially at night, and raise their kids to always be bear aware, including having an exit plan when they are walking around town and utilizing buildings and vehicles to stay safe. Participants generally shared that living with polar bears is a normal part of life and emphasized that if the bears are respected, they will reciprocate that respect. The Cree, Dene, and Métis participants expressed they have the utmost respect for Inuit culture related to polar bears, and specifically Inuit rights to harvest polar bears for cultural, economic, and subsistence purposes.

Episode Four

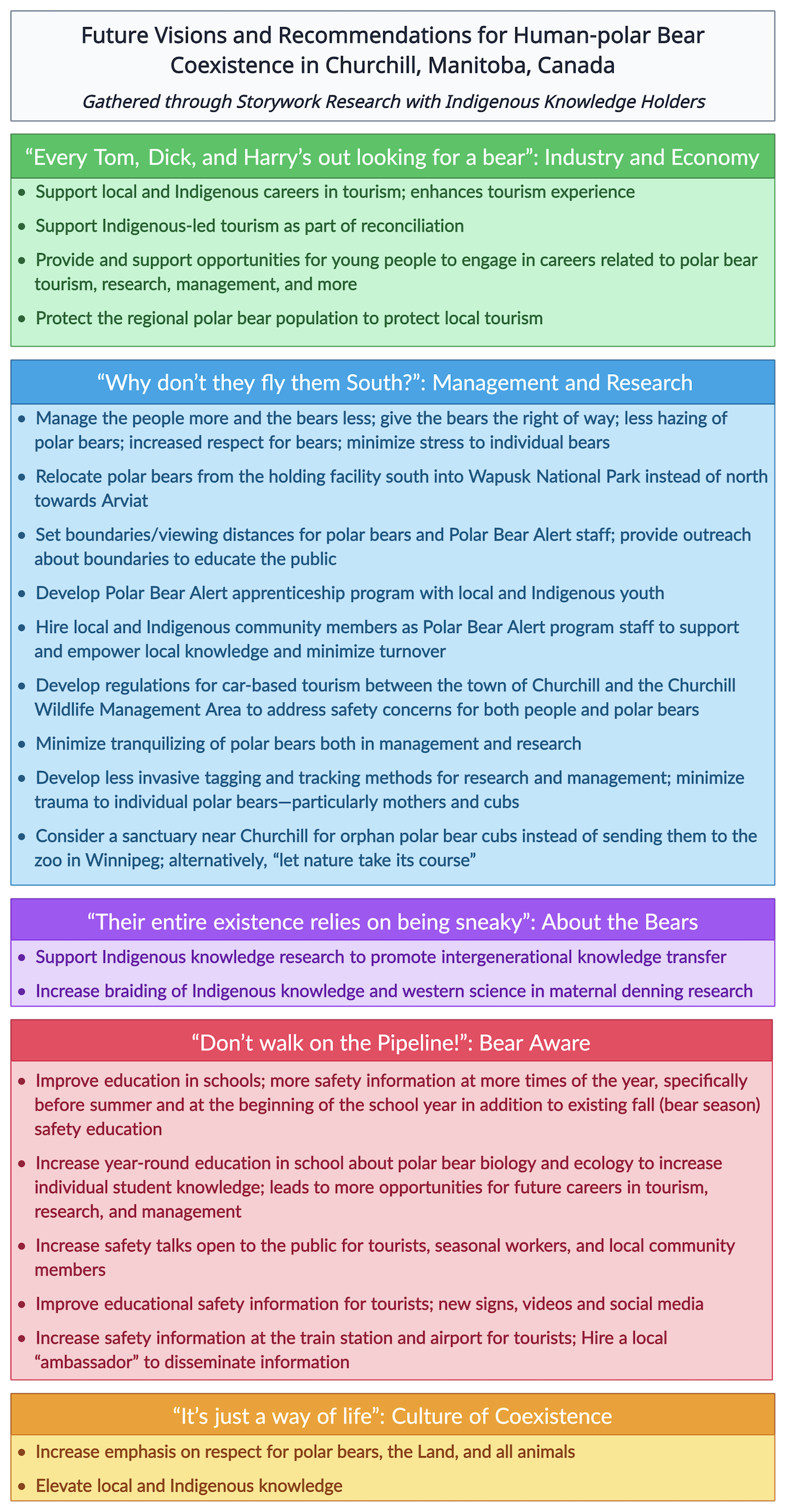

Participants had many visions for the future of human–polar bear coexistence in Churchill, which synthesized into the five main themes includes:

— Protect tourism as an important industry and economy

— Support proactive management and less invasive research

— Elevate Indigenous knowledge in research and management

— Improve bear safety education and awareness

— Cultivate a culture of coexistence

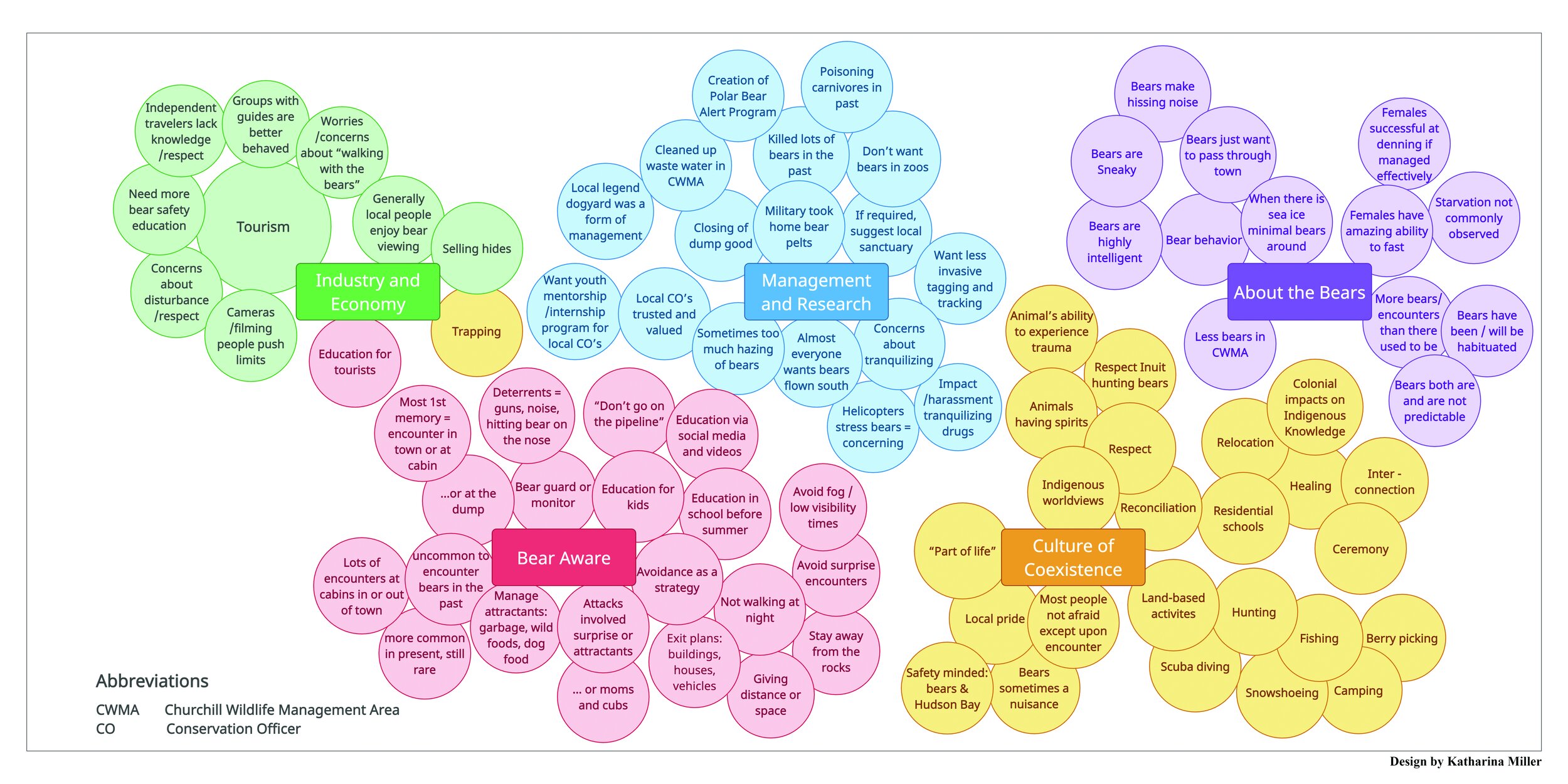

More detail regarding future visions articulated by research participants can be found in the figure below.

Future Visions & Recommendations

“That bear’s going to pay the price for somebody’s stupidity of trying to get a picture, and I don’t think it’s fair.” — Research participant

“How, the problem bears, when they take them out of jail and then they fly them north. I would like to know, like, is that really the best idea? Because I remember when Arviat didn’t really have a bear problem, and now they have a bear problem. Is it because we’re putting all of our bears there? Maybe there’s a better spot to take them, like maybe into the National Park, because that’s a big area where people don’t live.” — Métis participant

“Tourists need to be educated more.” — Cree Elder

“The coexistence thing is pretty critical, and it’s quite unique.” — Cree Elder

“I’m trying to help other Indigenous peoples all across the country to recognize that tourism is big business, and it’s part of reconciliation, that can bring us back, and be used as an economic driver for our communities.” — Métis Elder

“Knowing the way people personally react to stress: it can affect the way we sleep, the way we eat, the way, like, our day-to-day life continues. I can only assume that it’s probably the same for different types of animals and species around the world.” — Research participant

“They should have, like, some sort of apprenticeship program, for the next [Conservation Officers], it should be young local people following in their footsteps...” — Cree participant

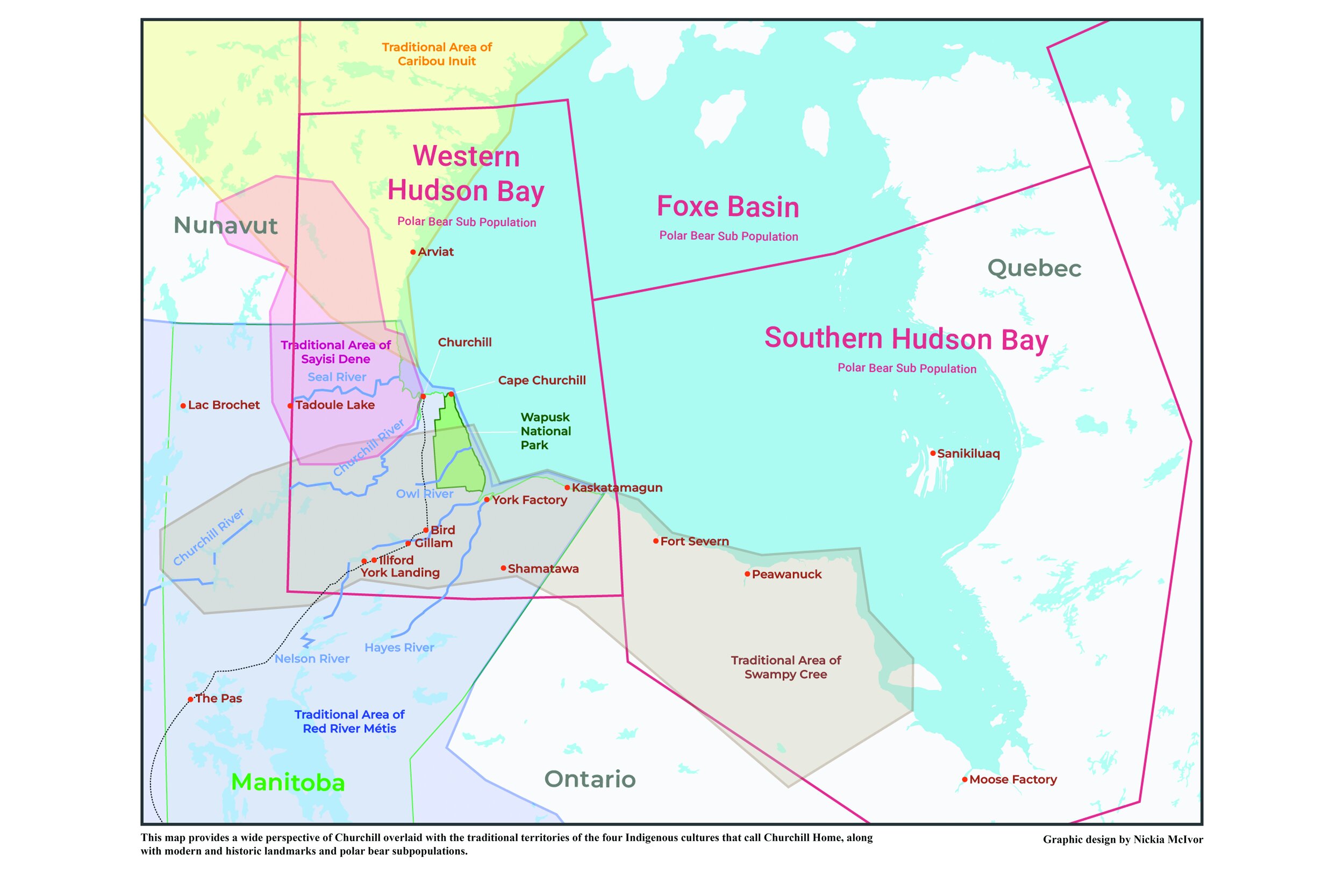

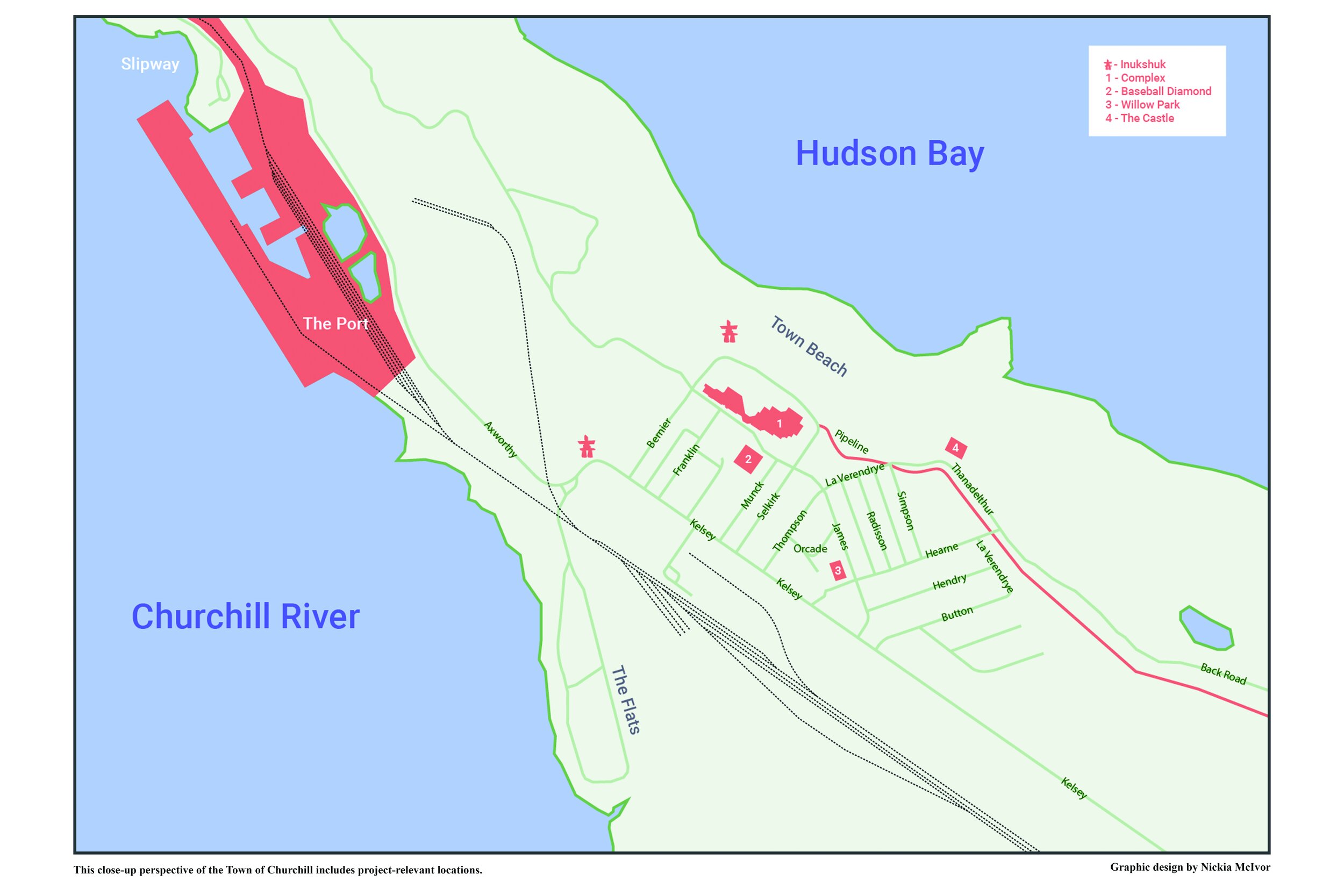

See this map larger

See this map larger

See this map larger

The above maps of the Churchill region were coproduced to provide additional context for the knowledge shared. Graphics cocreated and designed by © Nickia McIvor

Photo: Kt Miller / Polar Bears International

Research Design

“This research was intentionally designed to braid Indigenous ways of knowing and western social sciences throughout the project, beginning with the ethical considerations all the way through theory, methods, analysis, and dissemination of results. Working with the Indigenous Knowledge Keepers, the mayor of Churchill, the participants, the community, and a Cree Elder, Georgina Berg, as my co-researcher has been an honor and a true joy.” – Researcher Kt Miller

Analysis

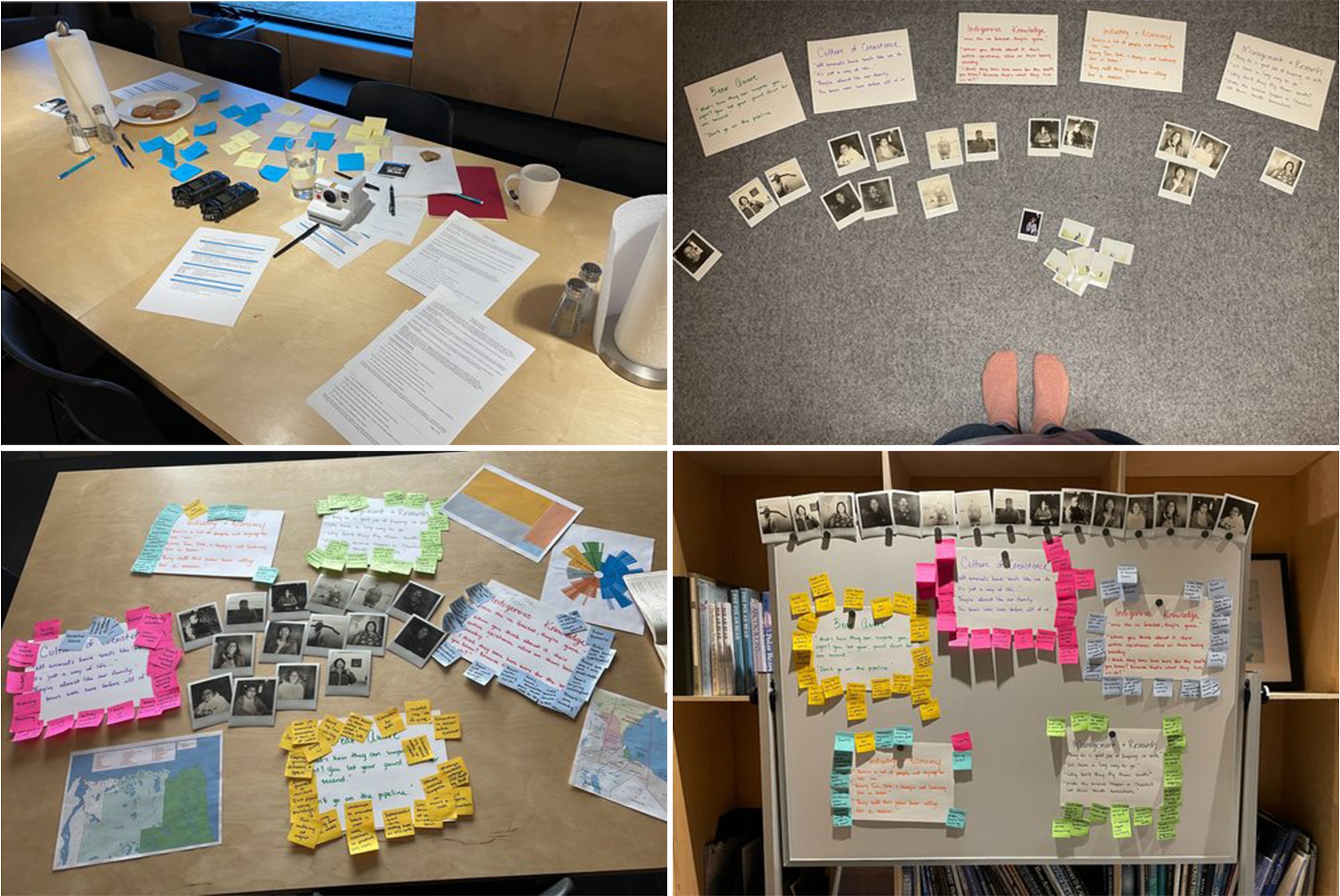

Reflections from researcher Kt Miller

On my second visit to the community for this research project, Georgina and I were discussing the process ahead. We had both been journaling over the summer, simultaneously, thousands of miles apart. Chapter 8 of the journaling book that we were following instructed us to go back to the beginning of our journals and circle the themes. When Georgina and I were together again in Churchill I exclaimed, “You’re already a researcher! That is what we are doing, that is how we will analyze our research, we will essentially go back through everything and look for, or circle, themes.” It was a moment of synchronicity and coproduction of knowledge that I will never forget.

See this graphic larger

Throughout the analysis I went back and forth between audio editing software, social science coding software, and post it notes. The data was coded, or organized into inductive themes (patterns) and time based themes (distant past, past, present, and future). I returned to the community once to validate the inductive themes, and a second time to share and validate the podcast episodes. Each podcast is a storyline that weaves the inductive themes (patterns) with the time periods (deductive) that were significant in the context of the community and human-polar bear relations and interactions. Huge thanks to David Borish for sharing his video-based qualitative analysis method which inspired and informed this data analysis.

See this graphic larger

Community Presentation

Community feast and presentation in Churchill, Manitoba, Canada on October 7, 2023. Filmed and edited by Roy Mexted / Churchill Entertainment.

This research project was co-created by Katharina M. Miller, Georgina Berg, The Indigenous Knowledge Keepers of Churchill, Manitoba, and Michael Spence with guidance from Dr. Michael Lickers, Adjunct Professor & Indigenous Scholar in Residence at Royal Roads University and Dr. Dominique Henri, Research Scientist at Environment and Climate Change Canada.

This research project was approved by the Royal Roads University Research Ethics Board and followed the Principles of OCAP®—the First Nations principles of ownership, control, access, and possession—asserting that First Nations have control over data collection processes, and that the research participants in this study granted permissions for all aspects of this study and own and control how this information can be used now and into the future.

This research project was made possible with funding from Polar Bears International and Environment and Climate Change Canada.

This research is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0