Photo: Kt Miller / Polar Bears International

Barents Sea Polar Bears

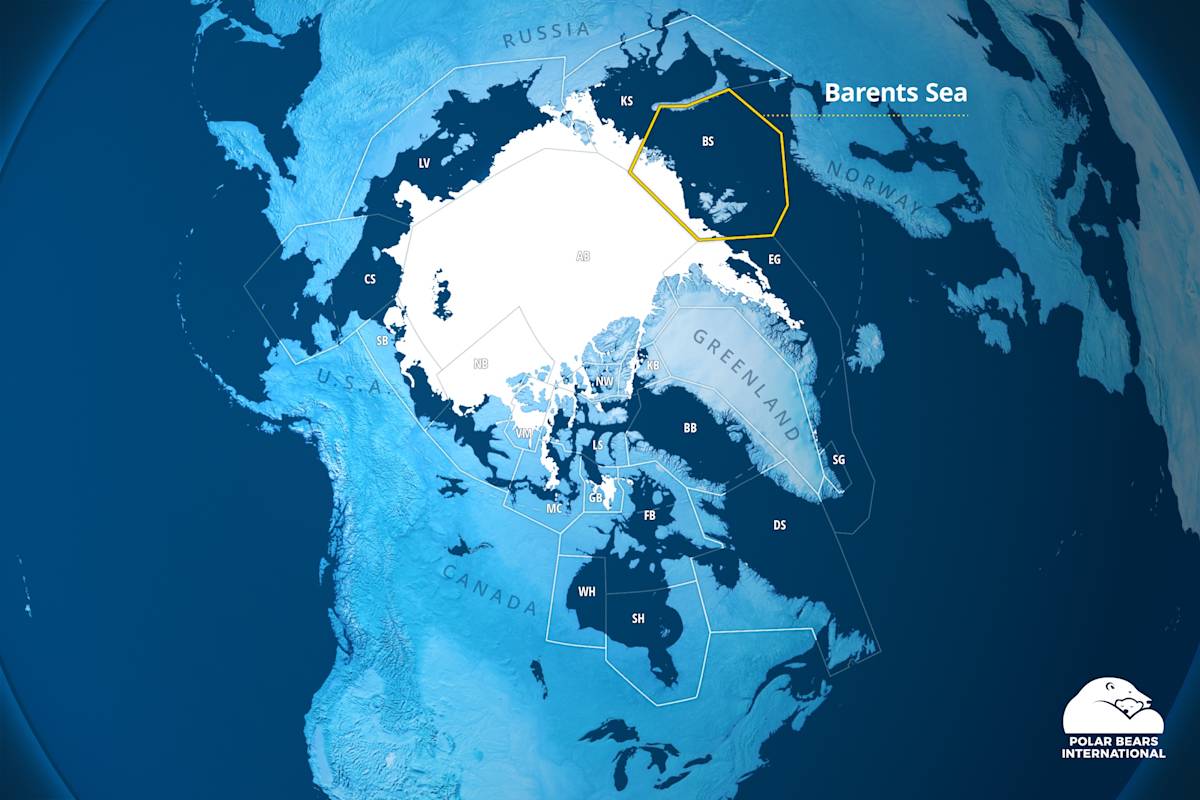

The Barents Sea polar bear population, shared by Norway and Russia, is one of 20 in the world. It makes up about 10 percent of the estimated global population.

An Interesting Population

As with polar bears elsewhere, the Barents Sea polar bears prey primarily on seals, particularly ringed seals. Also, like other polar bears, they face threats from declining sea ice due to climate change. But there are some differences that make the Barents Sea bears an interesting and special case.

Photo: Daniel J. Cox

Range and Numbers

The Barents Sea population borders the Eastern Greenland population to the west and the Kara Sea bears to the east. It includes bears on Svalbard, Norway, in the western Russian Arctic—specifically, the Franz Josef Land archipelago—and the sea ice between them and to their north. In 2004, a joint Norwegian-Russian survey estimated approximately 2,650 bears in the population, roughly 1,000 of them in Norwegian territory. About 250 of these were found on Svalbard, with a similar number counted during a 2015 survey of the Norwegian side of the population.

A History of Hunting

Beginning in about 1870, Norwegian hunters killed or captured approximately 300 bears, mostly on Svalbard, every year for a century. In the 1960s, scientists expressed concern about the impact on polar bear numbers, and in 1973 Norway ceased hunting polar bears after signing the international Agreement on the Conservation of Polar Bears. (The Soviet Union had banned commercial hunting in 1956.)

Given the number of bears killed, it has been estimated that the Barents Sea population numbered about 10,000 bears before hunting began. It is believed that the population rebounded rapidly in the first decade after hunting stopped and subsequently grew more slowly or stabilized.

It is unclear why numbers today are far short of the pre-hunting estimate. One factor may be that hunting figures include bears from other populations that migrated into the Barents Sea. It is also possible that the carrying capacity— the number of animals an ecosystem can support—has decreased, or that recovery is being limited by factors such as pollution or climate change.

Photo: BJ Kirschhoffer / Polar Bears International

Two Types of Bears: Coastal and Pelagic

Barents Sea polar bears are in what is known as the Divergent Ice Ecoregion, where ocean currents continually carry ice offshore as it forms. This movement is especially noticeable in summer. As the weather warms, new ice stops forming and the remaining ice drifts north, leaving a gap of water between land and the polar ice pack.

In response, bears in the Barents Sea adopt two principal strategies to find food. The "coastal" bears stay on and around Svalbard and hunt seals close to shore. These 250 or so bears have among the smallest home ranges of any polar bears—as little as 185 square km. They feed primarily on ringed seals on landfast ice (ice that is “fastened” to the coast) and glacial ice in fjords. Most of their feeding takes place in spring, after ringed seals have pupped and when food is most abundant.

The larger group consists of "pelagic "bears that head out onto the ice pack, traveling out to sea with it and wandering large distances in search of food. They hunt over a wider area (almost 400,000 square km) and for longer periods. This is because food is more dispersed on the sea ice than in coastal areas.

Whether a bear is a coastal or pelagic bear appears to depend on which path its mother took. Cubs born to coastal bears generally also become coastal bears. Indeed, a bear born in north Svalbard tends to remain in north Svalbard, while a bear born in the southern part of the archipelago is more likely to live most of its life there.

Polar bears roam across the circumpolar Arctic, where they rely on sea ice to reach their seal prey. But not all sea ice is equal. Learn about the four sea ice ecoregions, how the quality of sea ice differs across the polar bear’s range, and how we can help ensure the bears’ future by addressing climate change.

A Relatively Varied Diet

As with polar bears elsewhere, the most common prey of Barents Sea polar bears is the ringed seal, the Arctic’s smallest seal. Because ringed seals tend to occur in higher density on nearshore ice, they form a higher percentage of the diet of coastal polar bears in the Svalbard area. Pelagic polar bears in the Barents Sea eat ringed seals, but also hunt larger bearded and harp seals.

Coastal bears in Svalbard are also known to prey on reindeer, bird eggs, and vegetation, although to what extent is unclear. It seems likely that polar bear predation of reindeer has increased in recent years, partly because reindeer numbers on Svalbard have rebounded from a low of perhaps 500 after they were protected from hunting, and partly because declining sea ice means bears are forced to spend more time on land. However, there is no reason to believe that such alternative food sources can provide anything like the sustenance offered by the region’s seals.

Denning Bears

When it is time for polar bears to give birth, they dig dens in the snow. Svalbard—along with Wrangel Island off Russia, and southwestern Hudson Bay in Canada—is home to one of the most concentrated polar bear denning areas in the world.

Polar bears build dens across Svalbard, but most commonly in the eastern part of the archipelago. Dens are generally within 10 km of the coast, close to areas of fast ice where ringed seals give birth to their pups, giving mothers and cubs the best opportunity to find as much food as possible when they emerge. Cubs and their mothers spend their first year close to shore in areas of high ringed seal numbers. Only when the cubs are older do pelagic bears follow their mothers out onto the ice.

Photo: Daniel J. Cox

Barents Bears and Climate Change

Because polar bears rely on sea ice, they are at risk from a disappearing ice pack due to climate change, and that is of particular concern in the Barents Sea. The annual average temperature in the Barents region climbed by as much as 2.7 degrees Celsius (4.9 degrees Fahrenheit) each decade in the past 20 to 40 years, making it the fastest warming area on Earth. Unsurprisingly, this has impacted sea ice in the region: the landfast ice around Svalbard has declined by 50 percent compared to 1973-2000 and the sea ice season is two months shorter than it was two decades ago.

For coastal bears in the Barents, this means the ice on which they hunt ringed seals is sparser and more fractured, forcing them farther inland to feed on bird eggs or reindeer or requiring them to spend more time in the water, swimming from floe to floe and attempting to leap out of the water and onto ice to grab seals. Although polar bears are highly accomplished swimmers, spending too much time in the water depletes their energy reserves; besides, such hunting techniques are far less reliable than stalking seals on the ice.

Another consequence of decreasing ice is that the ice edge is retreating farther and farther away from the Svalbard coast, and sometimes is not even returning in the fall when pregnant bears need to come ashore to den. That means those bears must either swim long distances to shore, again depleting them of vital fat stores they need when going without food while they give birth and nurse their young, or den elsewhere. There are indications that at least some bears are giving up on even attempting to reach Svalbard and are instead walking long distances over the ice to den on Frans Josef Land.

Coastal and pelagic bears are increasingly becoming completely separated from each other, resulting in less mating between the two groups and causing a 10 percent loss in genetic diversity in Svalbard bears over the last 20 years.

Photo: Kt Miller / Polar Bears International

Other Issues Facing Barents Sea Bears

While sea ice decline is the biggest issue facing Barents Sea polar bears, it is not the only one. The bears in this region also carry, on average, higher levels of chemical pollutants than those in Greenland or Arctic Alaska, and pelagic bears in the northeast of the population’s range have the highest levels of all. These contaminants include polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and brominated flame retardants (BFDs) that are carried to the region by winds and currents, accumulating in animals in progressively greater amounts as they travel up the food chain. Among other issues, they can affect the immune systems and thyroid hormones of marine mammals, including polar bears; because they accumulate in fat, they can be released into the organs and blood stream of pregnant and lactating females that are depleting their fat reserves while in their dens. They may also be passed to cubs through the mother’s milk. Bears that are already suffering energetic stress because of climate change are only going to become more vulnerable to such impacts.

What Polar Bears International Is Doing

Polar Bears International is funding and conducting a wide range of research and education efforts to help conserve the polar bears of Svalbard and the Barents Sea. One of our most important efforts is working with the Norwegian Polar Institute and the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance on a long-term monitoring program of maternal dens on Svalbard. Using remote, solar-powered cameras that have been refined over years of field testing, the study is documenting key aspects of denning behavior for polar bears and refining den emergence and den departure dates.

Building on earlier work in Alaska, the study will help answer the following questions for polar bears in an area that has been greatly impacted by sea ice loss:

How long it takes moms and cubs to emerge from maternal dens

How long polar bear families remain at den sites before journeying to the sea ice

How the bears spend their time after emerging

The body condition of both moms and cubs

How sensitive denning polar bears are to human disturbances

Near-term survival of cubs post-emergence

The findings will help managers and policymakers establish the best possible guidelines to protect moms and cubs. It will also help scientists understand the impact of climate warming on the timing of den emergence, survival rates of cubs and provide insights into the den-selection process.

The Future

Despite rapid warming and reductions in sea ice, the polar bear population in the Barents Sea appears to be relatively healthy today—some rare good news. Although data is scarce, particularly on the Russian side, population numbers appear to be stable; and, unlike in western Hudson Bay or the southern Beaufort Sea, scientists have not observed widespread deterioration in body condition in the Barents Sea polar bears or decreased cub survival. This is likely due to the rich, productive waters of the Barents Sea.

However, given the species’ almost complete reliance on sea ice, and the rapidity with which sea ice in the region is disappearing, the picture is highly unlikely to remain so positive. Decreases in genetic diversity are an early sign of a population feeling the stress of climate change. It is entirely possible that changes in Barents Sea polar bears will happen not gradually, but rapidly. It is vital that we urgently and significantly reduce our emissions of greenhouse gasses before summer sea ice in the Barents Sea disappears completely, leaving the area’s polar bears literally adrift.