Photo: Shannon Curtis

Status

Learn about the 20 populations of polar bears and how they’re faring.

Are Polar Bears Endangered?

The IUCN Polar Bear Specialist Group lists the polar bear as a vulnerable species, citing sea ice loss from climate change as the single biggest threat to their survival.

Photo: Daniel J. Cox

How many polar bears are there?

The IUCN estimates there are currently about 26,000 polar bears worldwide. But without action on climate change, we could lose all but a few polar bear populations by the end of the century.

Photo: Daniel J. Cox

Main Threats

In addition to climate warming, other challenges to the bears include increased commercial activities, conflicts with people, pollution, disease, inadequate habitat protection (of denning and seasonal resting areas), and the potential for over-harvest in smaller or declining polar bear populations.

When Will Polar Bear Populations Disappear?

In a new paper, released July 20, 2020 in Nature Climate Change, scientists forecast the future of polar bear populations based on two different carbon emissions scenarios.

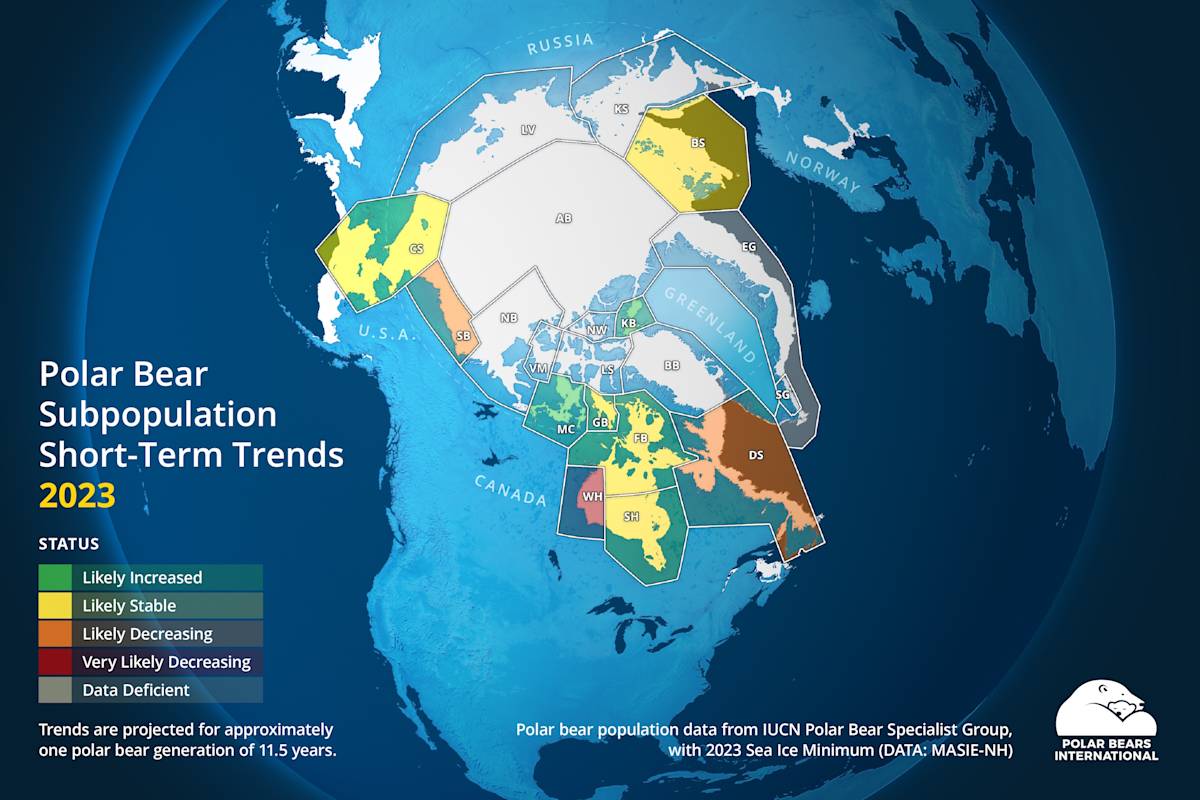

Status and Trends of the World’s 20 Polar Bear Populations

Arctic Basin (AB) Data deficient

The AB subpopulation is a geographic designation to account for polar bears occurring in the most northern areas of the circumpolar Arctic that are not clearly part of other subpopulations. The total number of bears that use the AB region, and whether these bears are residents or transients, is unknown.

Baffin Bay (BB) Data deficient

Due to evidence that the sampling design and environmental conditions likely resulted in an underestimate of abundance in the 1990s, the estimates of abundance for the 1990s and 2010s are not directly comparable and trend cannot be determined. Satellite telemetry analyses comparing movements of adult females in 1990s to 2000s indicate reduced seasonal ranges, increased isolation, 30+ days more on land on Baffin Island in summer, reduced body condition, reduced cub recruitment with early sea-ice breakup, and increased swimming.

Barents Sea (BS) Likely stable (2004 to 2015)

There has been no legal hunting of polar bears in Russia since 1957 and in Norway since 1973. Different sources of demographic studies suggest the population grew steadily after 1973, and at least until recently (ca. 2015; Aars et al. 2017). Recent habitat decline has led to late sea-ice formation in autumn around some important denning habitat, and in such years few females den in these areas. Den distribution may have shifted from east Svalbard to Franz Josef Land in most years. In 2015, the Norwegain portion of the subpopulation was surveyed. It was indicated that the number of local bears in Svalbard was similar to in 2004, and that more bears were on the pack ice. Possibly, bears could have shifted westward from Russian to Norwegian areas in the pack ice, thus an increase is not conclusive over the last generation. There is no evidence of large scale reduction in body condition.

Chukchi Sea (CS) Likely stable (2008 to 2016)

Estimate of subpopulation trend is from Regehr et al. (2018b). Independent estimates of abundance from a 2016 aerial survey (Conn et al. 2021) are larger than, but of similar magnitude to, the estimate of 2,937 from Regehr et al. (2018a). Indices of of body condition and recruitment from springtime research have been good, although autumn observations from 2004–2010 may suggest declining cub survival. Longer ice-free periods are increasing land use. Subsistence harvest is legal and monitored in the US. Harvest remains illegal and un-monitored in Russia.

Davis Strait (DS) Likely decreased (2007 - 2018)

Management objective to slightly decrease the subpopulation from the Nunavut jurisdiction resulted in increases to harvest quotas and an increase in harvesting in Quebec, where reporting is not mandatory, which may have contributed to the slight decline. Most recent analysis did not detect links between survival and various ice conditions in the study period (2005-2018). Longer ice-free periods may be increasing land use and driving concerns of increases in human-wildlife conflict.

East Greenland (EG) Data deficient

Reduction in sea-ice habitat quality has led to changes in habitat use based on telemetry analyses. A new assessment of the subpopulation began in 2014.

Foxe Basin (FB) Likely stable (1994 to 2010)

There are no estimates of vital rates. Harvest appears to be sustainable.

Gulf of Boothia (GB) Likely stable (2000 to 2017)

Change from multiyear to annual ice provides likely improved habitat productivity at present. Increased shipping could become a concern.

Kane Basin (KB) Likely increased (1997 to 2014)

More bears were documented in the eastern regions of the KB subpopulation area during 2012 – 2014 than during 1990s surveys which may reflect differences in spatial distribution of bears, possibly influenced by reduced hunting pressure by Greenland in eastern KB, but also some differences in sampling protocols between decades. Some caution should be taken in the interpretation of population growth. An additional estimate of abundance based on a springtime 2014 aerial survey in KB was 190 bears (95% lognormal CI: 87 - 411; Wiig et al. 2022).

Kara Sea (KS) Data deficient

There has been no legal harvest in the KS subpopulation since 1957. Amount of illegal hunting unknown.

Lancaster Sound (LS) Data deficient

Demographic data are >20 years old. Selective hunting for males in the harvest decreased due to the U.S. import ban and listing under the U.S. Endangered Species Act in 2009, but as of 2021 are nearly back to pre-ESA listing levels. Increase in shipping activities.

Laptev Sea (LV) Data deficient

There has been no hunting in the LS subpopulation since 1957. In 2018, a federal sanctuary (zakaznik) on the archipelago of the Novosibirsk Islands was created by a decree of the Government of the Russian Federation.

M'Clintock Channel (MC) Likely increased (2000 to 2016)

Potential for shipping activities. The subpopulation was managed for recovery with harvest below sustainable rates. Change from multiyear to annual ice provides likely improved habitat productivity at present. Harvest quota was increased to 21 bears per year for 2021/22 harvest season based on most recent abundance estimate.

Northern Beaufort Sea (NB) Data deficient

Declines in sea-ice habitat and observed and predicted declines in the health and abundance of ringed seals are of concern. Harvest is currently managed using the updated (ca. 2020) subpopulation boundary at 133° W between the Southern Beaufort Sea and Northern Beaufort Sea subpopulations. Sea ice metrics used in the status table reflect the updated boundary from 1979-2022. Current harvest rates are based on a managed subpopulation size of 1,710 bears reflecting (1) the revised subpopulation boundary, which increased the geographic area of the NB subpopulation (Griswold et al. 2017); and (2) potential negative bias in the current abundance resulting from incomplete sampling of the subpopulation (Stirling et al. 2011). A new subpopulation assessment is underway.

Norwegian Bay (NW) Data deficient

Initial population viability analysis simulations resulted in population decline after 10 years, although vital rates from the NW and LS subpopulations were pooled for the analyses. Projections of decline were also high because of small sample size. Current data are >20 years old; small population.

Southern Beaufort Sea (SB) Likely decreased (2001 to 2015)

The population-wide estimate of abundance from Bromaghin et al. (2015) reflects the previous SB-NB boundary at 122° W. The subpopulation trend reflects information presented in Bromaghin et al. (2021), which assessed survival and abundance in the U.S. portion of the SB subpopulation. Other data in the Status Table reflect the revised boundary at 133° W (updated ca. 2020), including sea ice metrics for 1979-2022. Concerns include declining body condition and increased frequency of fasting, periods of low survival, and growing reliance on land during summer, as identified in studies based on the previous eastern boundary delineation (Rode et al. 2018, Atwood et al. 2021, Bromaghin et al. 2021, Rode et al. 2022). An additional concern in Alaska is the growing potential for human-polar bear conflict arising from increased industrial development of the coastal plain (Atwood et al. 2020, Wilson and Durner 2020). A new subpopulation assessment is underway.

Southern Hudson Bay (SH) Likely stable (2012 to 2021)

Increased time onshore due to changes in breakup and freeze-up; declining body condition; declining survival rates, especially for cubs-of-the-year. The 2021 point estimate was at least 29% greater than the 2016 estimate. Distributional shifts from adjacent WH and population growth from decreased harvest mortality and improved recruitment are likely drivers of this increase. The years 2019 and 2020 were good ice years relative to the years prior to the 2016 survey.

Viscount Melville Sound (VM) Data deficient

Low densities of ringed seals and polar bears were observed during capture-recapture sampling conducted 2012–2014. Field sampling to estimate abundance was completed 2014. Analyses are underway but the final report is not yet available.

Western Hudson Bay (WH) Very likely decreased (2011 to 2021)

Concerns include harvest, increased time onshore due to changing dates of breakup and freeze-up, declines in body condition, and lower productivity. Earlier declines in size of subpopulation linked to reduced survival due to timing of sea-ice breakup. The 2021 point estimate of abundance was 26.7% lower than the 2016 estimate and partially due to temporary movement of some bears to SH as well as diminished vital rates.