The late Dr. Ian Stirling was a member of the Scientific Advisory Council for Polar Bears International. He was also Research Scientist Emeritus for Environment and Climate Change Canada and Adjunct Professor of the Department of Biological Sciences, University of Alberta.

With the exception of family groups, most polar bears on the sea ice are solitary, traveling extensively over home ranges that may vary in size from a few thousand to hundreds of thousands of square kilometers. This makes extended observations of the undisturbed behavior of wild polar bears difficult to obtain but extremely valuable when opportunities arise.

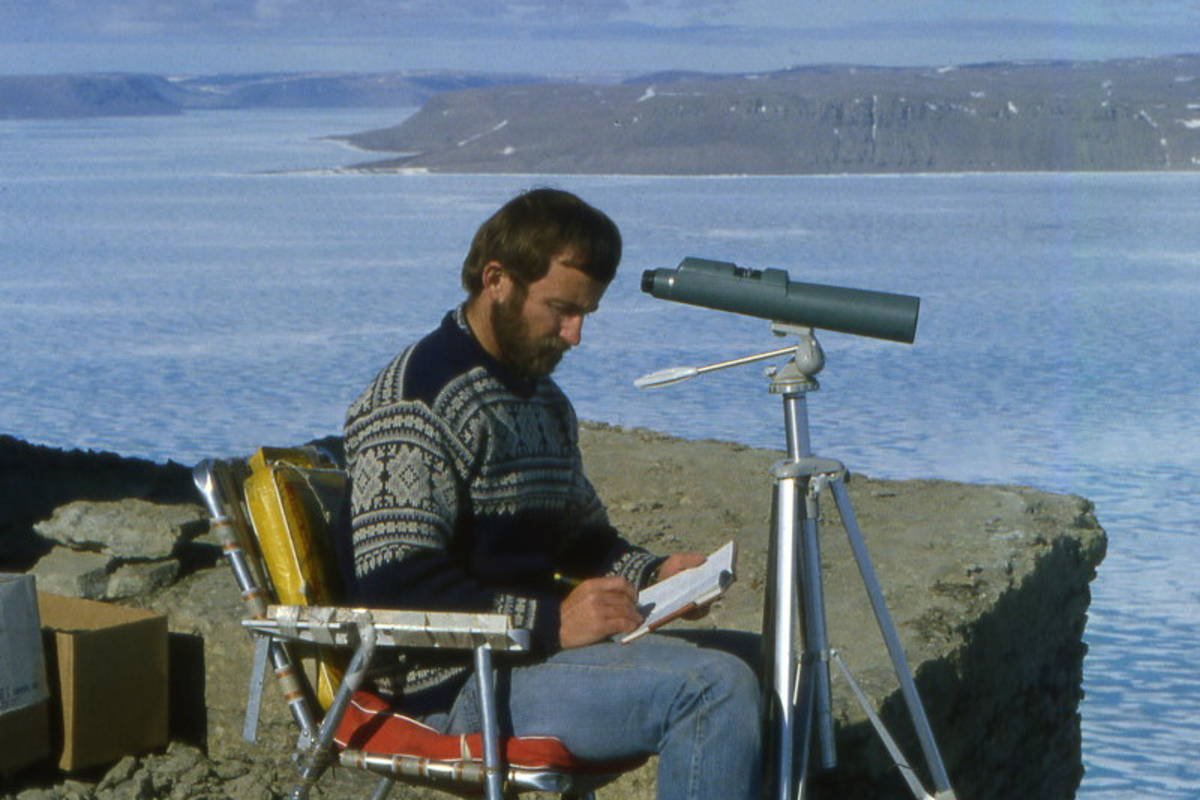

For several years, beginning in 1973, I led a study to observe the undisturbed behavior of wild polar bears—hunting, interacting, sleeping, and otherwise just being bears. Collectively, scientists were already accumulating vast amounts of information on polar bear movements by observing where tagged polar bears were recaptured relative to where they were first captured and, later, from the use of satellite radio collars. Similarly, we obtained a great deal of new information from body measurements and specimens collected from bears while they were briefly immobilized for tagging.

However, I felt it was still critical to understand what polar bears spent their time doing when they were not disturbed by scientists in helicopters or Inuit hunters. In other words, I wanted to just let the bears show us, at their own speed, what it meant to be a wild undisturbed bear on the sea in the Arctic.

To do this, we used telescopes from cliff-top observation cabins at Radstock Bay, Devon Island, in the Canadian High Arctic that were high enough that the bears were unaware of our presence. Because of 24-hour daylight in the late spring and early summer, we could watch the bears continuously. Often, we had to take turns between watching inside (and sometimes out in the cold) and sleeping in an unheated tent outside the observation hut. We recorded observations of individual bears non-stop, as long as they didn’t step behind distant land forms or have their visibility obscured by fog.