It is not surprising that most people first think of polar bears when contemplating the rapidly disappearing sea ice in the Arctic due to human-caused climate warming. The reasoning is both straightforward and logical. Even children in elementary school know that polar bears find it difficult to catch seals in the open water; they depend upon the presence of sea ice as a platform from which to more easily hunt them.

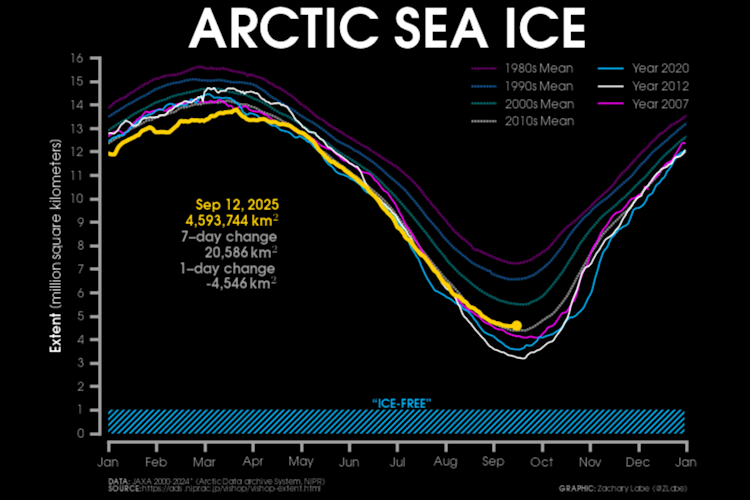

Consequently, as the sea ice breakup comes earlier and earlier, while freeze-up gets progressively later, the duration of the open water period through which the bears have to survive on their stored fat reserves, without being able to catch more seals, gets longer and longer. In the Barents Sea around Svalbard (the Norwegian Arctic) for example, the number of ice-free days per year is now increasing at the staggering rate of 65 days per decade (Parkinson 2014). The negative effects of sea ice loss because of climate warming on some populations of polar bears, such as those in Western Hudson Bay and the Southern Beaufort Sea, are clear and have been well documented. But, what about the ringed seals—the polar bear’s most important food source—in a steadily warming Arctic?

Many people assume that as long as sea ice is present during part of the year, there will be lots of seals and, if the polar bears have a platform to hunt from, everything will be fine. But, could it really be that simple? Our knowledge of the status of most seal populations in the Arctic, but especially the all-important ringed seal, is rudimentary at best. However, we do know enough about the breeding ecology of ringed seals, the primary prey species of polar bears, to clearly identify some huge concerns. In fact, it is abundantly clear that the negative effects of climate warming on ringed seals in much of the Arctic are already dramatic. Ultimately, what happens to ringed seals is the most important single factor in how climate and the loss of sea ice impacts the polar bear.

Throughout the winter and spring, ringed seals live beneath the solidly frozen ice along the coastlines and in the bays throughout the Arctic. They self-maintain their breathing holes by scratching the re-freezing sea ice with the claws on their fore flippers (Smith and Stirling 1975). In fact, each seal maintains several holes so that, if a polar bear discovers one, the occupant may be able to escape and breathe safely at a different one.

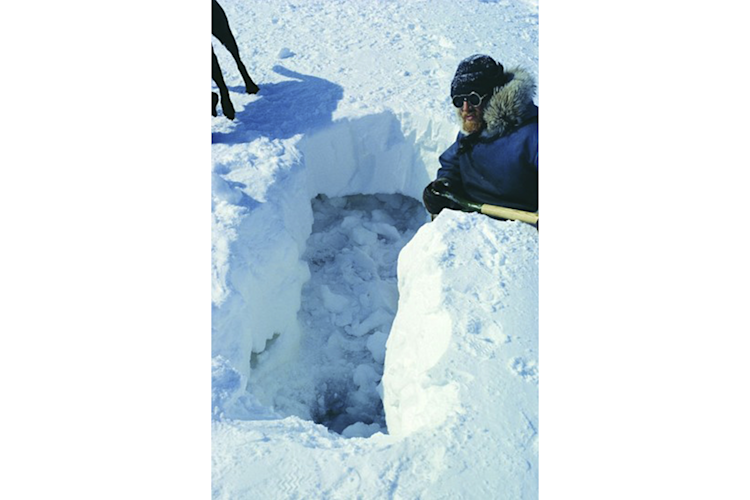

In about early April in most areas, pregnant female ringed seals give birth to their pups in small birth lairs; they dig these in snowdrifts that form over one of their breathing holes during winter (e.g. Figure 1).