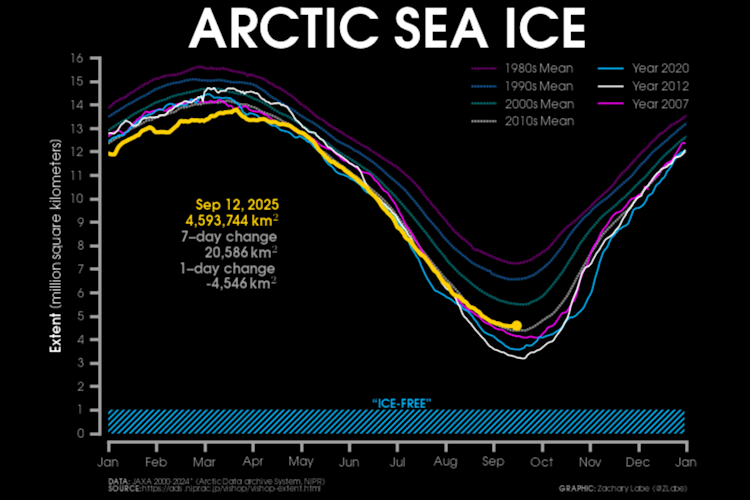

Last year observed the 2nd smallest extent of Arctic sea ice in the satellite history. This was accompanied by unprecedented warmth across Siberia that persisted for nearly every month of 2020. In fact, a recent study found the heatwaves over that region would have been nearly impossible without human-caused climate change.

Unusual fall

The massive area of open water north of Eurasia and abundantly sunny skies led to an increase in the absorption of heat in the upper layers of the Arctic Ocean by the end of last summer. The warm ocean and strange weather conditions further contributed to the latest sea-ice freeze-up on record in the Laptev Sea. At one point in October, the total extent of Arctic sea ice reached the largest absolute anomaly on record – more than 3,000,000 square kilometers below average or greater than the size of India!

As sea ice continued to slowly refreeze, all the heat that accumulated in the ocean during summer escaped into the overlying atmosphere. This led to the warmest November on record for the Arctic Circle. By the end of December, the sea ice had reemerged across most of the Siberian Arctic and finally bringing an end to the historic autumn freeze season.

Winter extremes

2021 started off with a remarkable change in weather conditions both at the surface and high in the atmosphere. A sudden stratospheric warming (SSW) event occurred in early January, which happens when the polar vortex dramatically weakens in the upper levels of the atmosphere over the Arctic. Although this spectacular meteorological event takes place high in the stratosphere, it can also have a significant influence on winter weather that directly impacts people across North America, Europe, and Asia.

So far, 2021 is no stranger to extreme events. As a result of the weaker polar vortex, record cold escaped into North America and contributed to the coldest February in more than 30 years across the contiguous United States.

Meanwhile, closer to the Arctic, unusual warmth continued across the Barents-Kara Seas with temperatures nearly 10°C (18°F) above average. And, after almost a year of record heat, colder temperature anomalies returned to the Siberian Arctic.

Interactions between the weaker polar vortex (stratosphere) and conditions in the troposphere (e.g., the jet stream) remained a significant driver of regional weather patterns through the end of winter. Although the late-winter warmth in the Arctic was certainly less extreme than recent years, the annual sea ice maximum still fell to the 9th lowest on record (March 2021).

Summer melt season

Despite colder temperatures returning to the Eurasian coast by mid-late winter, unusual atmospheric conditions in spring contributed to another record start to the melt season in the Laptev Sea. Average June 2021 sea-ice extent in the Laptev Sea was the smallest on record. Keep in mind that the previous record was set just last year! Recent research has found that excessive warmth in the deep ocean may also be enhancing ice loss in this region, but this remains an active area of research.