Exactly how many bears pass through Churchill and environs varies, as is evidenced by the number of bears that are handled by wildlife officers each year. (That is, how many bears enter the town itself and are physically captured and/or taken to the holding facility, popularly known as the Polar Bear Jail.) In 2003, that number was 173; four years later, it had fallen to 49, the fewest in over a decade, but in future years it would tumble: 37 in 2018, 24 in 2019. In 2020, 2021, and 2022, the totals were just four, 10, and six - although in 2023, the number increased again, to 24.

One reason for that decline, says York, may be a change in human behavior in Churchill – specifically, how residents deal with their trash. Until 2005, the town’s garbage, including food waste, was piled up and burned in an open-air dump, which unsurprisingly proved a strong attraction for bears. The closure of the dump resulted in a decline in the bears that required handling, and with the passage of time, all the bears that used to visit it or remembered its existence have now died. As a result, far fewer of the Western Hudson Bay bears have any positive association between the town and food and so more are inclined to bypass Churchill itself on their way to the ice. In addition, Churchill has introduced bear-resistant garbage bins in recent years, further reducing attractants.

Tragically, in April, the town's waste storage and recycling center was destroyed in a blaze. That means that, at least for now, residents must once again stockpile their waste on the surface of the landfill for future burying. While it is surrounded by a hard fence, the scents serve as a powerful attractant to wildlife, including polar bears. Additionally, in the interim more garbage is being stored temporarily near residences, which could also draw hungry bears.

But other factors play a role. Most notably, there are significantly fewer polar bears in the Western Hudson Bay population than there used to be. In 1987, the population was estimated to be 1,200; by 2004 that had fallen to 935, while the most recent survey, results of which were published in 2022, produced an estimate of just 618.

The principal reason for that, of course, is that warming temperatures are causing the sea ice in Hudson Bay to melt earlier and form later, leaving polar bears with less time to hunt, and causing a decline in the size and health of bears as well as their survival and reproduction rates. But while the overall trend is clear, there are short-term wrinkles: between approximately 2016 and 2022, for example, changes in the polar vortex actually led to ice in Hudson Bay lasting until later into the summer. As a result, the bears stayed out longer and the currents deposited them farther along the coast, away from Churchill; when the ice formed again, many of those bears may have elected not to make the long trek back, almost certainly contributing to the lower numbers of bears entering town during that time.

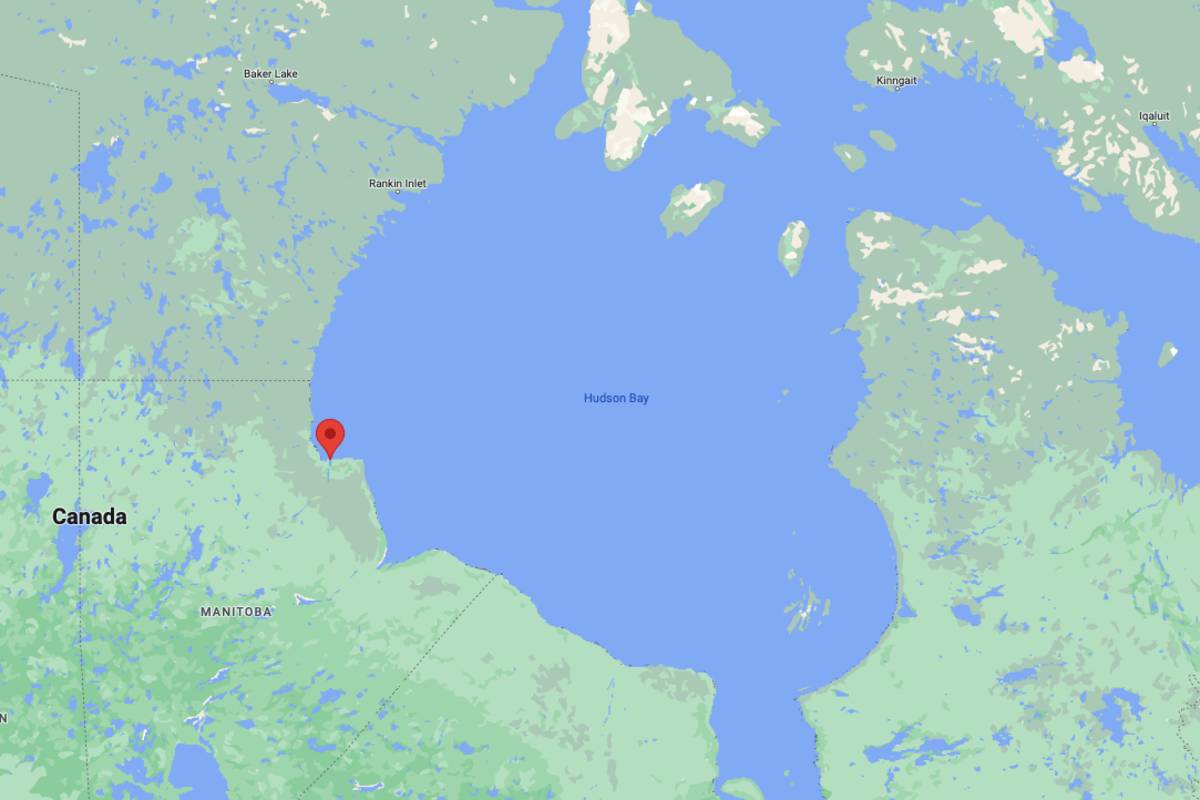

Conversely, in 2024, currents pushed sea ice away from the coasts of southern and eastern Hudson Bay quite early, causing it to pile up far to the west. This created historically low ice conditions for Southern Hudson Bay while Western Hudson Bay was full of ice quite late in the season. What that will mean for polar bear numbers in Churchill this season remains to be seen, but in the community of Arviat, approximately 150 miles north, a late raft of sea ice has resulted in an influx of bears and a decision to keep Halloween celebrations indoors this year.

So, many factors affect exactly where the Western Hudson Bay polar bears come ashore when the ice melts and how many gather near Churchill when it forms again. The future of the population is uncertain; but for now, Churchill remains probably the single most accessible place to see polar bears in the wild, for researchers and tourists alike. Hopefully, if we take the necessary steps to greatly reduce greenhouse gas emissions and put the brakes on global warming, it will remain a popular spot for polar bears and people alike for many, many years to come.

Kieran Mulvaney is a freelance writer who has written extensively about polar bears and the Arctic for publications including National Geographic, The Guardian, and The Washington Post. A native of Bristol, England, he lives in Bristol, Vermont.