Winding security lines; daily COVID testing; eyes smiling above masks; wishes for our future chalked on sidewalks; news cameras and spotlights; 100,000 people marching in the rain; synthetic blue carpets; business suits; speed walking; a mother and two daughters; voices elevated; voices absent; voices silenced; young leaders coordinating across borders; indigenous leaders calling for justice; weary looks exchanged; people caring for people; a giant illuminated globe spinning dizzily overhead.

These are a few scenes I watched unfold in and around the United Nations Conference of the Parties (COP26) in Glasgow, Scotland this fall. Polar Bears International sent a delegation to the climate summit, attending as official Non-Governmental Organization (NGO) observers to the negotiation process.

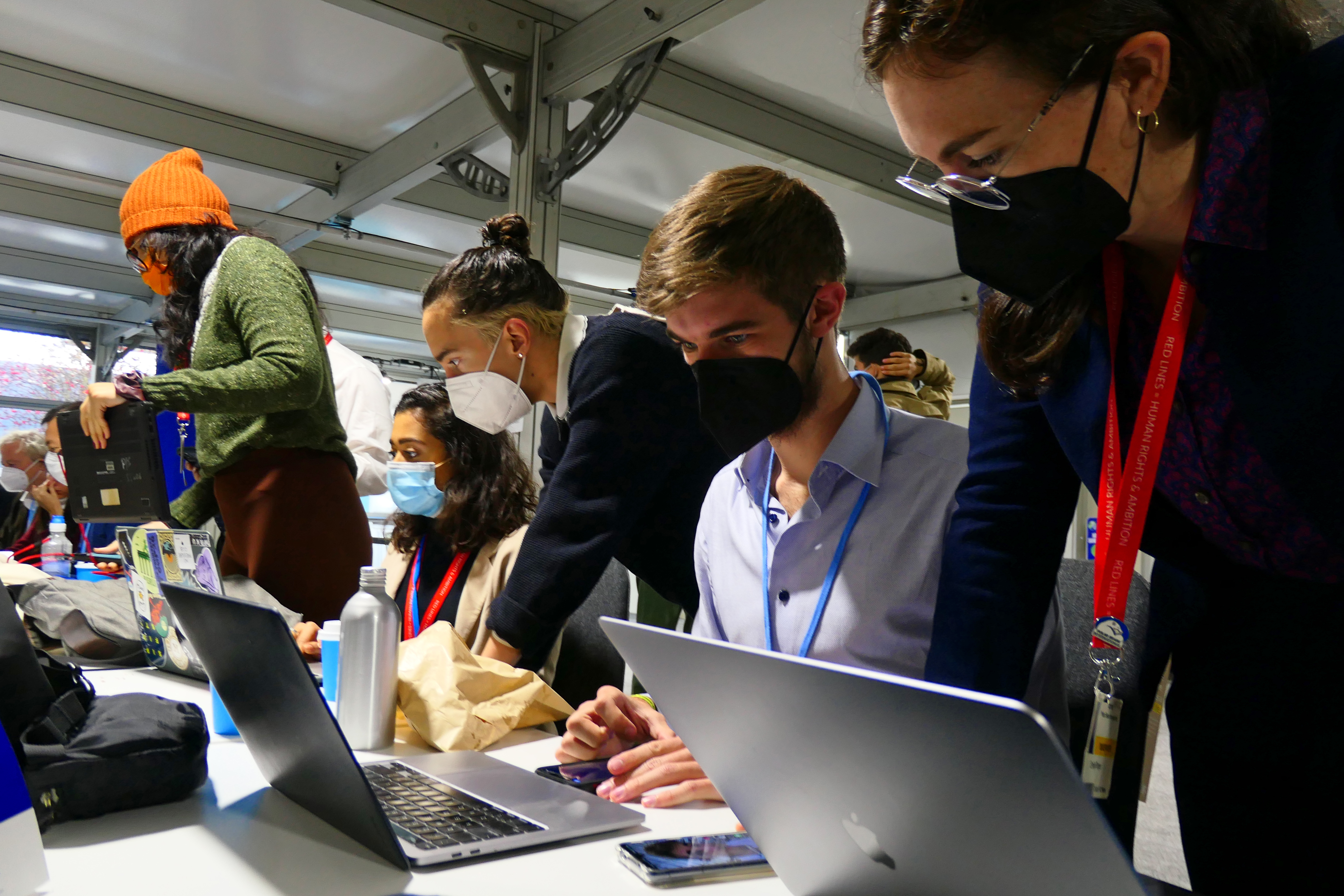

Why attend as observers? NGO and civil society participants provide an important balance to government delegates at these conferences—voicing the needs of frontline communities, representing goals that transcend national interests, and offering expert and focused knowledge about global environmental issues. Through a combination of funding support and shared accreditation badges, Polar Bears International helped nine members of our global civil society—including community leaders, scientists, communicators, and university students—attend this important decision-making space, forming a powerful youth contingent.

The results of COP26 were intensely mixed, and many demands made by communities who are already experiencing devastating impacts of climate warming went unanswered. On the opening day, Elizabeth Wathuti shared stories of starvation and drought in her home country of Kenya, asking leaders to “Please open your hearts. If you allow yourself to feel it, the heartbreak and the injustice is hard to bear.” Witnessing the dissonance between what global citizens needed from COP26 and what was delivered weighed heavy on my conscience and soul.

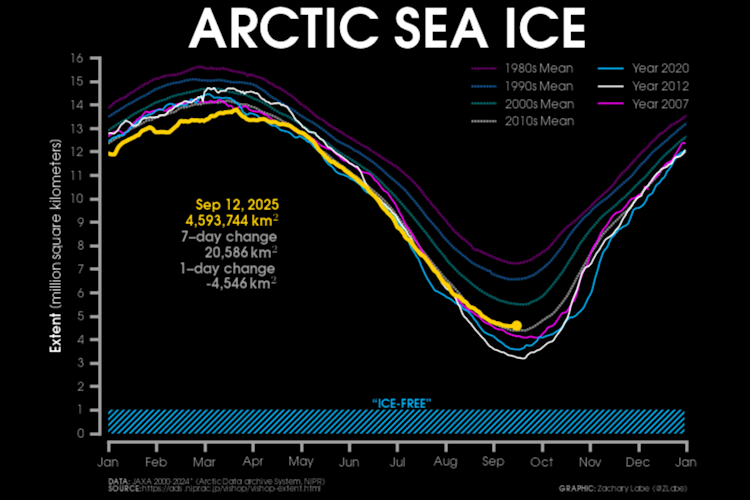

The Glasgow Climate Pact moved the global climate plan needle, but current commitments will not secure a livable future for polar bears and most of us on this planet. During the conference, many informal and non-binding promises were made by countries and businesses. If these promises are turned into action, the future looks a bit brighter.

While the commitments made in Glasgow fall far short of what is needed to conserve critical sea ice habitat for polar bears and keep warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius, reaching this goal is still possible. The sliver of hope lies in action at the local level and in the Glasgow Climate Pact’s request for countries to come back in less than a year with more aggressive commitments. Keeping the pressure up to ensure governments make those commitments is an important next step for all of us. (See the end of this article for a high-level overview of technical COP26 outcomes.)

Standing on the other side of COP26, I am torn between incompatible realities. On the one hand, incremental climate policy and promises are wholly inadequate for the urgency of this crisis, a challenge with a scale unlike anything humans have addressed before. On the other hand, I also recognize that COP26, alone, was never going to be a complete solution.

This reality is not as bleak as it may sound, though. Global talks are necessary, but the hope for making progress at the speed we need lies much closer to home and therefore much more within our grasp.

As I settle back into my home in the United States—the largest historical emitter of greenhouse gases—I am reminded of my country’s responsibility in this crisis. The commitments made in global negotiations mean little if we cannot meet those goals with on-the-ground national and local policy. In other words, democracy needs to be a full contact sport, 100% of the time. Voting and elections are deeply important, but citizen engagement does not end there.

Protecting what matters to us—vibrant communities, clean air, safe homes, healthy wildlife and ecosystems—means applying pressure from all fronts, at all times. We have the power to animate our governments, corporations, and societies to lead. We can help pull our communities into a different and more promising future.

It is a funny feeling to be in a life that is unfolding in a permanently changed world. Accepting and addressing this reality is painful, and that pain can be a generator of great strength if we allow ourselves to feel it. For polar bears and all life on this planet, every reduction, every fraction of a degree counts. The hope we need to keep stepping forward in the face of uncertainty will not be bestowed on us—we create it. We are the antidote to this malady.