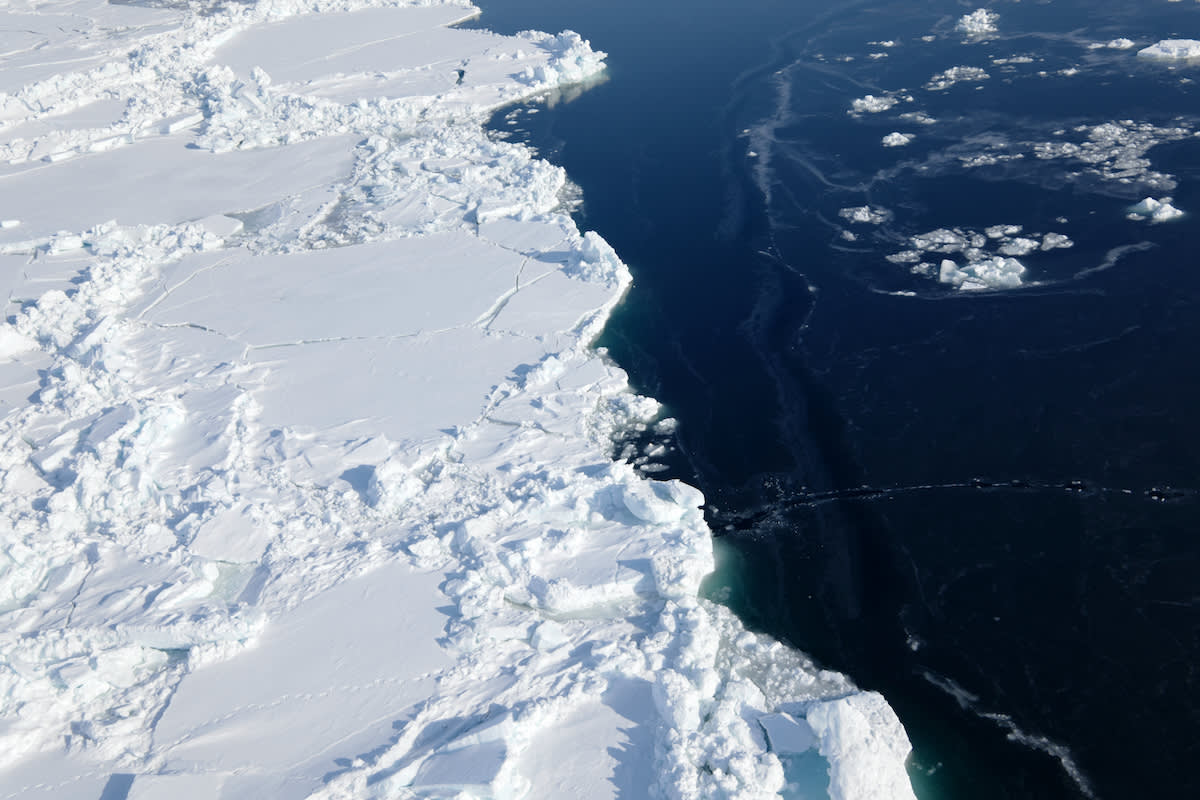

Few places are as remote and wild as the habitat that polar bears call home, but it’s also one of the most challenging places to study them. While many people have seen polar bears up close and personal near Churchill, Manitoba during the autumn migration, the density falls dramatically when the bears disperse onto the sea ice to hunt seals. There, they work hard to regain the fat they need to undergo the summer ice-free period when food is scarce or, for most bears, non-existent. The sea ice is where polar bears make their living and if one wants to understand them, it’s best to study them where they work and less so where they holiday.

Spring 2022 gave my research program the chance to return to gain new insights into the natural and unnatural history of the bears out on the sea ice. Two years of research were lost to the pandemic, and this interrupted my on-ice research in Hudson Bay. The focus of this study is to understand the relationship between polar bears, seals (ringed and bearded), and sea ice in a warming Arctic.