While on board the Tundra Buggy – which was amazingly silent as Frontiers North Adventures has been converting its fleet to EVs – the group discussed the nuances of responsible tourism in polar bear communities with differing cultural contexts. Participants from the Svalbard Museum and Visit Svalbard elaborated on Svalbard’s history – from its lack of an Indigenous population to its transition from whaling to coal to a tourism-focused economy – and tourism today, as visitors come to experience its glaciers, fjords, aurora borealis, and wildlife. There were some audible gasps from Canadians as Norwegian participants spoke about new Svalbard regulations that keep people at least 500 meters – or five football fields – away from polar bears.

As tourism operators and community members grapple with regulatory changes like these, how can they encourage the government to hear their concerns? Change begins from scaling up individual efforts, and Churchill successfully impacted provincial and national change by uniting local voices. The Churchill Bear Smart Working Group brings together Churchill residents, tourism operators, city government officials, and other interested people to discuss polar bear management with each other and the higher levels of government. Likewise, a concerned group of Churchill’s beluga whale tourism operators came together to impact the area’s whale-watching rules.

Expanding responsible tourism helps polar bear conservation and coexistence, as it reinforces the value of protecting polar bears. As some Northern Ontario participants foray into the indigenous-lead tourism sector – such as Gooseberry Tours in Peawanuck – they discussed the need for more education on non-lethal deterrence methods, and how a working group model may help with coastal community collaboration and standardized training on polar bear encounters.

Deterrence Training

By the last day, it was time for participants to get their hands on some practical deterrence methods, highlighting the wide variety of tools for less-lethal interactions with polar bears. The group tested non-lethal approaches including handheld flares (which you’re often able to find at a marine supplies store), bear spray (which is effective even in the cold– though it helps to keep it warm in your coat, and to be mindful of the wind’s direction and speed), and different types of less-lethal ammunition, from rubber bullets to noise crackers.

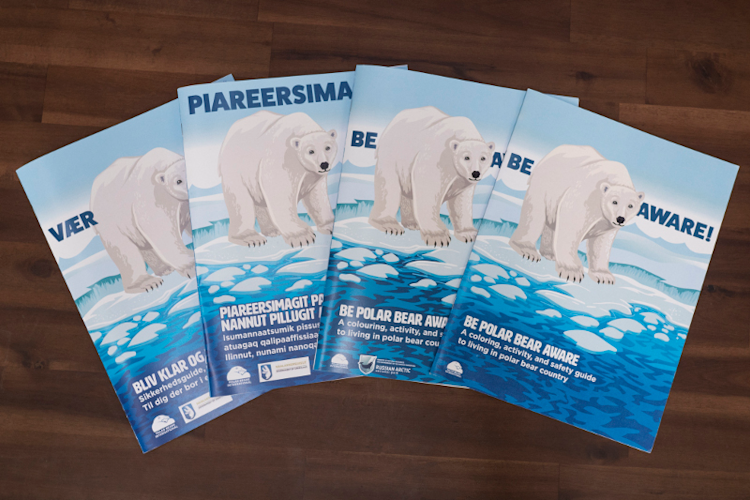

You don’t need to be a sharpshooter to effectively use bear spray or handheld flares, you just need to keep them in easy reach when you’re in bear country. Like anything, deterrence is all about context – weather, distance, the bear’s temperament, and local regulations – so there’s a toolkit of options. In Norway, for example, bear spray is still illegal – but handheld flares are easily available, and a great alternative to relying on a rifle. And as tourism brings more visitors to the North who may not be particularly comfortable using firearms (like myself), they need to learn about bear safety – through a safety video or pamphlet on arrival – and know both when to carry a bear deterrent and how to use it.