The Pikialasorsuaq (The Great Upwelling) Expedition set out in May 2022 to explore, document, and better understand the ecology and physical processes that make the North Water Polynya, an area of open water surrounded by seasonal sea ice, the biological engine of the Canadian High Arctic, with the goal to bring this story back to Canadians and the world.

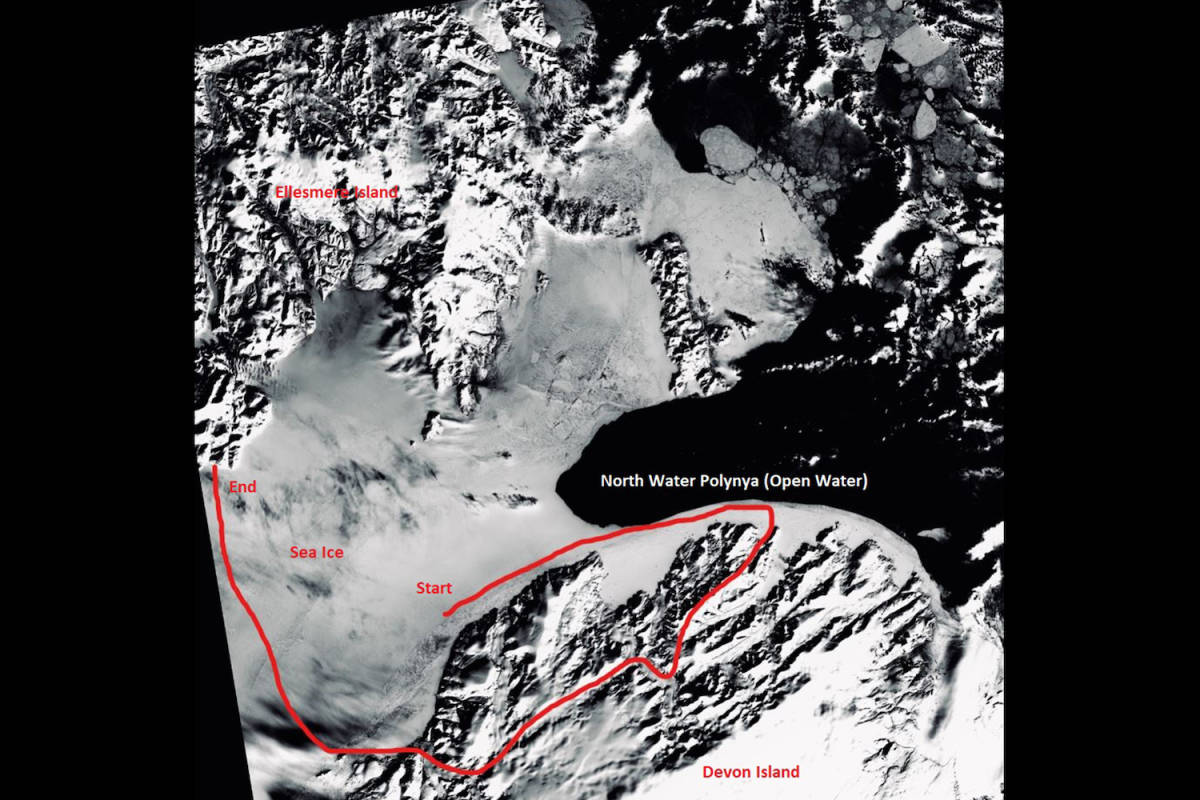

The expedition was a success, with John McClelland and Frank Wolf joining me, traveling 310 kilometers over 21 days, self-supported by ski, through sea ice habitat off the northeast coast of Devon Island, over the Devon Ice Cap, and returning to Ellesmere Island (Ausuittuq) after a 75-kilometer crossing of Jones Sound. The team was able to travel to the edge of the polynya, at times 6 kilometers off land and 20 meters from the open waters of Baffin Bay, an area they named “The Wild Edge of Canada.”

A better understanding of the ecology and physical processes shaping the region, including predator-prey dynamics, thermohaline circulation ocean dynamics, and the impacts of freshwater inputs (river and glacial run-off) on primary production were a few of the major successes of the journey. The team saw first hand how critical sea ice is to the overall functioning of the Arctic ecosystem, embedding themselves in core polar bear habitat for weeks. Through connections with Qikiqtaaluk Inuit and the team's personal experience, the expedition members better understand how changes in the quantity, quality, and spatial extent of sea ice are impacting Inuit travel, hunting, and inter-community relationships.