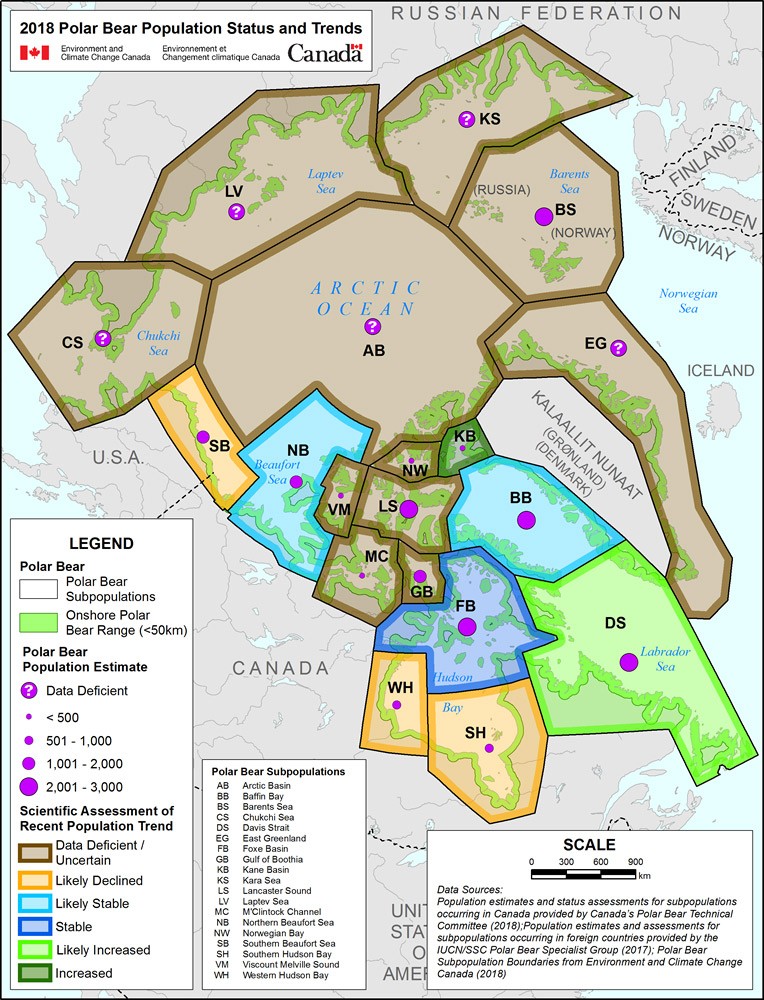

Take a look at a population status map for polar bears and you can’t help but notice that the entire Russian coast is marked as “data deficient.” In fact, the vast Russian Arctic contains the least studied polar bear populations in the world.

It’s easy to see why. Conducting research in the Russian Arctic is logistically difficult and historically quite expensive. Basic infrastructure—including small aircraft and reliable fuel depots—are often lacking or restricted. In addition, many of Russia’s polar bears are shared with other countries. This creates additional challenges, from Internal security concerns to barriers posed by shifting international politics.

Despite these hurdles, recent partnerships and novel approaches have led to new opportunities.

In light of these developments, Polar Bears International is helping to fund two key research projects focused on polar bear populations shared by Russia and other countries, one in the Barents Sea and the other in the Chukchi Sea. Both are biologically rich areas thought to have large populations of polar bears. The studies will help scientists fill data gaps, leading to a better understanding of how these bears are faring.

Barents Sea Project

Russia’s Barents Sea polar bear population is shared with Norway. These bears have experienced a massive loss of sea ice habitat over the last few decades, a trend predicted to continue. A few hundred of the bears in this population remain in Norway’s Svalbard archipelago year-round. But the majority migrates between Svalbard, Russia’s Franz Josef Land, and the pack ice areas north of the islands.

Thanks to a long-term monitoring project by the Norwegian Polar Institute (NPI), the polar bears that range within Norway’s borders are well-studied, with data going back to 1987. However, very little is known about the Barents Sea bears that live in Russian waters.

This study will focus on whether the population is able to maintain its genetic diversity in the face of substantial sea ice loss. The NPI began collecting DNA samples from polar bears in Norway in 2003. Their initial research showed that:

Most of Svalbard’s polar bears ranged in the same local areas over generations.

Daughters usually chose maternity den sites in the same areas as their mothers. However, some looked for alternative den locations when the sea ice failed to connect more remote islands to the pack ice.

Historically, close inbreeding has been rare, despite male and female polar bears remaining in local areas over generations.

Females typically mated with different males, within a single year and over different years. This ensured high genetic diversity.

Large-scale gene exchange between local Svalbard bears and migrating bears ensured a large effective population size.

Given the rapid changes in sea ice in Svalbard, scientists anticipate significant changes in mating systems, including increased local isolation and the possibility of decreased gene exchange between local and migrating bears. More restricted interaction between bears from different areas may lead to increased inbreeding.

This study will focus on answering those questions by analyzing DNA samples from polar bears in Norway, Russia, and Greenland.