How can people take part in Beluga Bits?

There are two ways that folks who are passionate about belugas and the ocean can get involved and encounter these whales virtually. The first is to collect snapshots of belugas from the Explore.org Beluga Cam in July and August. The second way is to help classify the Beluga Bits images here. The workflows on Beluga Bits sometimes change to reflect different research interests, but many involve identifying the beluga’s orientation (e.g., can you see its underside?), what parts of the beluga are visible, and distinguishing markings on the belugas themselves. The Beluga Bits community is so keen that we occasionally run out of data to classify. If that happens check back often as we will have new data or workflows you can help us with.

How did Beluga Bits begin?

Like many projects, Beluga Bits started with a lot of questions about beluga whales followed by putting the pieces together to make it work. I had been studying belugas and other Arctic marine mammals for a few years and happened to be working on another project in Churchill with Meagan Hainstock looking at beluga behavior. While we were out on the water, we would get these tantalizing glimpses of belugas who had scars and marks that we thought could be used for photo identification, a common way to study other whales non-invasively.

Typically, with other whale species, you can use markings on the dorsal fins or the contrast of their body color with scarring to help identify them. Belugas on the other hand are much harder to identify given that they don’t have dorsal fins and are white as adults. While we were in Churchill and chatting with colleagues at Polar Bears International, we were introduced to the Beluga Cam.

It didn’t take very long watching the live stream to realize that this could be an amazing data source for capturing the full body images of beluga whales underwater. In fact, we realized we could often see a lot more than just the individual marks—because the beluga would often swim upside down, we could see their “bits” and determine if they were male or female, and thus Beluga Bits was born. It still took a couple of years to get to where we are today with the Explore.org community collecting snapshots that we then use in our Zooniverse.org project to get folks from around the world to help with classification.

In what ways has the project developed in the seven years it’s been running?

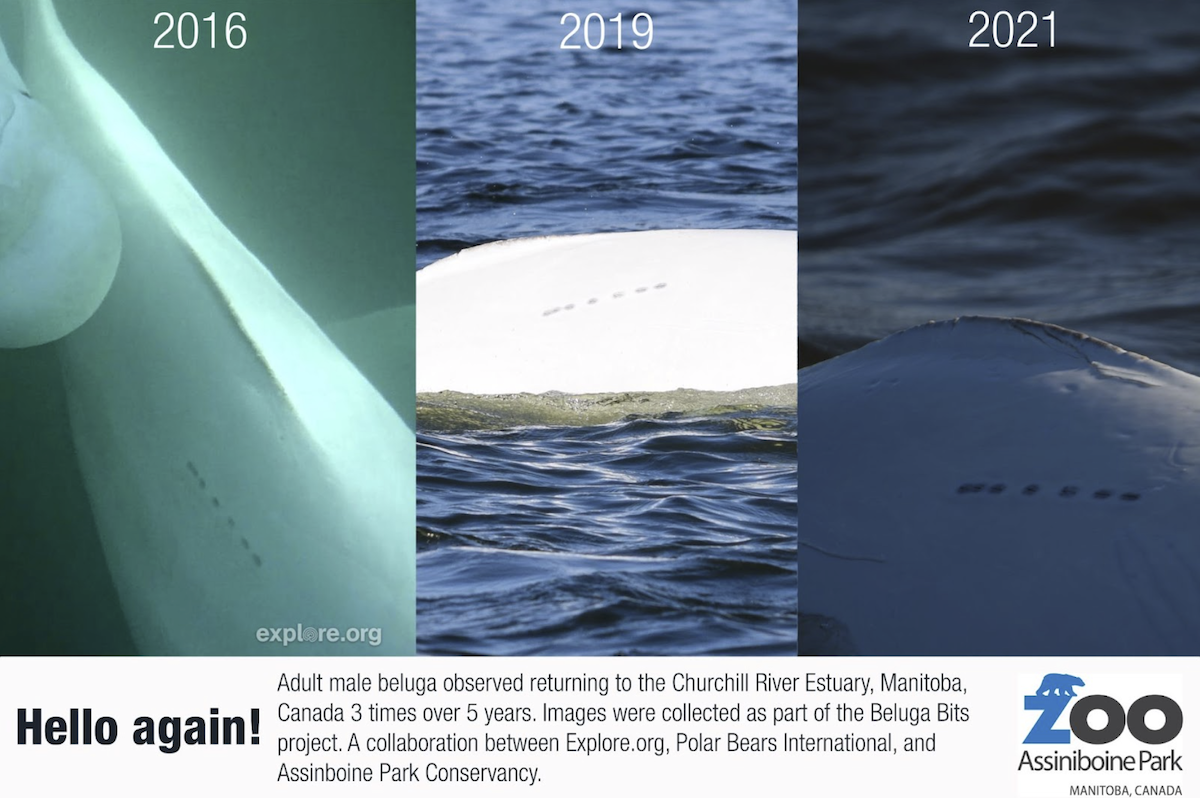

Our project has grown in scope every year since 2016. On Beluga Bits, we now have over 25,000 registered participants who have completed nearly 5 million classifications! There have been upgrades and changes to almost every aspect of the project. Our longstanding partnership with Polar Bears International has ensured incredible video footage every year, but they have also been able to expand video collection to other parts of Western Hudson Bay in addition to the in-estuary footage. An exciting development we have incorporated recently is the use of artificial intelligence, specifically machine learning, to help remove photos without belugas before uploading. Too many photos of just water are not that fun for participants to sort through and AI can quickly do this boring task. We partnered with a computer science professor and a student at the University of Manitoba to create an algorithm that can automatically detect frames that contain belugas, and those that do not. We have been using this algorithm since 2021 to pre-sort images that are ultimately uploaded to Beluga Bits.

Are there any new research questions your team is pursuing?

One cool development has been the need to develop a workflow dedicated to jellies and jellyfish species in the estuary. Many of our participants started pointing out interesting jellyfish in the beluga images so we wanted to explore these species further. This workflow started with three species we knew of, the moon jellyfish, the lion’s mane jellyfish, and the Arctic comb jelly. However participants quickly started pointing out other individuals that looked different. We now have been able to confirm five species in the estuary, adding the melon comb jelly and the common northern comb jelly to our list. In fact this project was the first to document northern comb jellies this far south in Hudson Bay. We are particularly interested in monitoring jelly and jellyfish populations as these species can be indicators of ecosystem change in ocean habitats. As the Arctic ocean warms and there is increasing ship traffic, we may start to see new species of jellies and jellyfish appear in this environment. It’s important that we monitor these species as they may provide greater insights into the ecosystem and emerging threats.