With almost 3000 participants from more than 70 countries, and 250 presentations over the course of three days, the Arctic Circle Assembly is the single largest gathering of Arctic residents, researchers, politicians, activists, and observers in the world. Each year, attendees gather in the beautiful Harpa Conference Center in the Icelandic capital of Reykjavik to listen to or participate in briefings and discussions on an almost staggering array of topics. This year’s meeting, from October 14-17, was no exception.

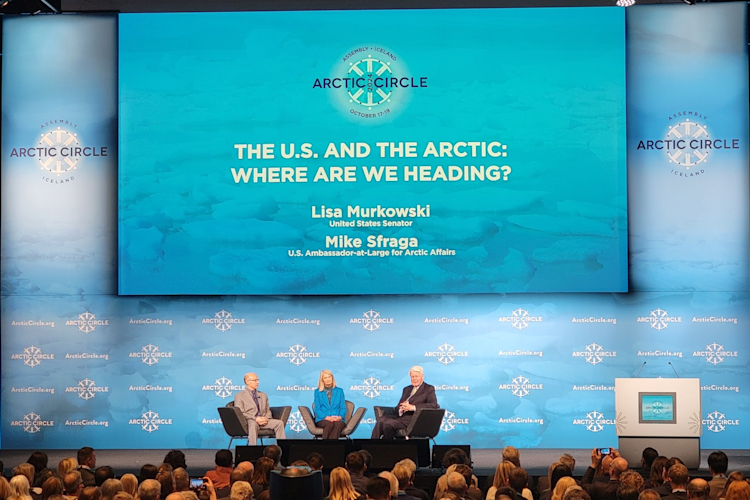

Session topics ranged from the broad-based to the detailed. Afternoon plenary sessions often saw heads of state and other dignitaries discuss big-picture issues such as the Arctic policies of China and the United States or the role of NATO in the Arctic, while smaller morning and evening sessions tended to focus on more nuts-and-bolts topics like regulating Arctic tourism and management of solid waste in remote Arctic communities.

Many of the attendees were from governments and think tanks in Arctic states as well as countries such as Singapore and South Korea that are very far from the Arctic but which, courtesy of their involvement in international shipping, view a warming, melting Arctic with interest. Military uniforms were as common as traditional Sámi clothing, testament to the sheer variety of attendees the conference attracted.

Geopolitics still top of mind

Overall, however, there were two predominant themes to this year’s conference. The first was geopolitics, and it’s worth noting that this year’s meeting was significantly less suffused with anxiety than that of 2022. Then, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was recent and raw, resulting in Moscow’s exclusion from most Arctic forums and raising concerns about what that portended for future cooperation in the region.

That was of particular concern with regard to the Arctic Council, the intergovernmental body that comprises all eight of the region’s nations as well as major Indigenous groupings and is by far the most important forum in the region. Each member country takes a two-year turn as Council chair, and with Russia in that position at the time, the organization’s immediate future seemed grim. Since then, however, the gavel has been in the hands of Norway, and Norwegian ambassador Morten Høglund revealed in Reykjavik that, while political meetings have not resumed, Russian experts have been participating virtually in some working groups.

But concerns over Russia’s behavior, and its potential impact on Arctic governance, remained a constant undercurrent, as did discussions over China’s Arctic ambitions, both of which overlapped with the other overarching theme, which might be summed up simply as infrastructure.