The buzz and rumble of many thousands of scientists thunder around downtown San Francisco. The city’s characteristic clinging fog does little to cloud the mighty minds spilling into the glass-walled chambers of the sprawling Moscone Center. Only a few weeks prior, global leaders including President Biden and China’s Xi Jinping met across these very same blocks to discuss economic policies affecting nearly 40% of the world’s population. Yet the topics of concern this week might be even more important. All these folks—many of the world’s leading geophysical researchers, practitioners, policy experts, and students—have descended on San Francisco for the same reason: to share findings concerning the study and protection of planet Earth, our one and only home.

There’s nuance, of course. This conference—the 2023 edition of the American Geophysical Union’s (AGU) annual December meeting, known as AGU23—is an international hub for earth sciences with over 25,000 attendees from over 100 countries. Hydrologists, atmospheric scientists, sea ice modelers, glaciologists, and biogeochemists are here in droves. With that lineup, you might picture the talks and meetings full of dry and confoundingly complex equations and graphs. And while those are definitely present, it’s clear this gathering is about much more than just science for science’s sake. Here too are policymakers, philosophers, funding agencies, teachers, physicians, Indigenous Knowledge holders, and community leaders. Like the scientists, they are also speakers, panelists, featured experts, and cornerstones of the AGU community. Such a plethora of perspectives breeds rich collaboration.

Three needs rise to the surface across the thousands of presentations, panels, town halls, and posters: 1) We need to better mesh research with the needs of communities—particularly those most underserved, 2) We need better ways to connect science and policy, and 3) We desperately need to immediately and rapidly accelerate actions to address climate change.

Photo: Kt Miller/Polar Bears International

Scientists have the solutions. They need us to make them happen.

By Alex Shahbazi, Guest Contributor

MINS

18 Jan 2024

Photo: Dr. Andrew Derocher

Science for more

In many ways, science as we once knew it is gone. In a good way. While there will always be a need for siloed experts plugging away at highly technical tasks whose descriptions would turn our “normal” brains to mush, science is becoming ever more focused on equitably answering the questions communities and society need to know.

These ideas are abundant across AGU23, realized through concepts like community science, co-production, actionable research, participatory science, and more. While all unique, they each center the needs of people and position communities as co-developers and guides in determining what knowledge research should prioritize and where and how it should be shared.

AGU23 examples abound. Researchers from the Alaska Center for Climate Assessment and Policy partner with tribal and municipal organizations to support food sovereignty and increase food security in Kake, Alaska, through community monitoring and other collaborative projects. An undergraduate engineering course at UC Berkeley takes student projects into the community of Stockton to co-design air quality improvements with local environmental justice groups. Climate modelers at the National Center for Atmospheric Research are co-producing data on wildfire and land use change with Indigenous communities in the Klamath and Yukon River watersheds. And the Southwest Crossing Community Initiative led community members, scientists, and advocates in understanding and controlling the impacts of a 300,000-gallon gasification facility that moved into a Houston neighborhood. These are only a handful among many.

To best sum it up, Ms. Margaret Gordon of the West Oakland Environmental Indicators Project urged a room of many dozens of scientists to remember that “communities aren’t for outreach, they’re experts.”

Photo: BJ Kirschhoffer / Polar Bears International

The line between science and policy

Scientists are trying to engage in policy, too. But it’s tricky. Traditional academic norms limit scientists’ involvement in decision making. They dictate, in general, for scientists to produce data and new findings that policy makers can then choose to use—or not use—to develop policies. Put more simply, there’s a line between science and policy, and traditionally scientists are told to maintain a wide berth. But perhaps, as with community science and co-production, those norms are shifting, too. Many experts at AGU23 are certainly pushing for it.

One multi-hour mega session underlines this excellently. Featuring a couple dozen presenters and panelists, the session can—in many ways—be summarized as scientists imploring their fellow scientists to put themselves on the front lines of climate policy advocacy. To use their personal time to assess politicians' environmental promises. To separate scientific objectivity from political neutrality. To even, if necessary, get arrested. After all, Dr. Sandra Steingraber tells the story of how more decision makers took notice of her data when she was incarcerated for protesting fracking than they did before.

Still, the line between science and policy is a tricky one. Lexi Shultz, AGU’s Vice President of Science Policy & Government Relations, encourages many to walk right up to that line without crossing it and actually say what needs to be changed based on what you’ve discovered. She also points out that the line is often a lot further away than one might think. To bring action all the way, though, takes more. Kei Koizumi, Principal Deputy Director for Policy at the Office of Science and Technology Policy, insists that science doesn’t tell us what we should do; the should instead comes from us citizens in a democracy.

Consensus says that science and policy need to be better connected.

The un-elephant in the room

And then there’s the un-elephant in the room, the ever-present threat that looms over all of us but is also in constant focus: climate change. Squint your eyes a little and AGU23 will start looking, in part, like a climate conference. But of course, when you’re a scientific community that sees dataset after dataset describing how human activities will continue to escalate ravaging impacts on the planet, how could it be anything else? A fever pitch of eco-anxiety crackles through the thousands of earth science experts. It’s unnerving.

But from the fear emerges hope. Oodles of it. These scientists and practitioners aren’t wallowing in despair but instead driving forward countless solutions. They’re leading projects to restore mountain forests, building solar panels, and bringing stories of climate impacts to the public. They’re developing novel techniques for removing emissions from agriculture and researching nature-based solutions to promote climate adaptation. They’re piloting and promoting local and global geoengineering projects and climate interventions to complement carbon reductions and accelerate us towards net zero emissions. And they’re amplifying the voices and autonomy of the communities most impacted through ever-proliferating climate justice actions. Now they need us to make these solutions happen.

Photo: Kt Miller / Polar Bears International

… And what about polar bears?

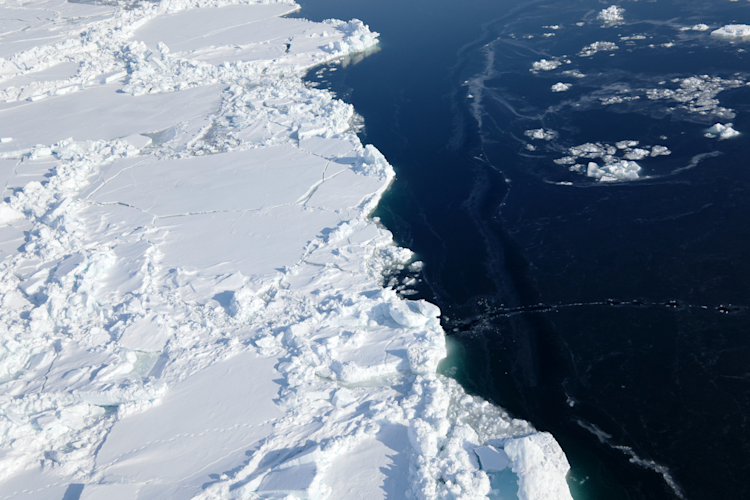

But why does this matter to polar bear conservation? You’re reading this article via Polar Bears International, after all. Simply put by Amy Cutting, Polar Bears International’s Vice President of Conservation: “By helping to sustain the polar bears’ future, we’ll help improve conditions for people, too. Our futures are intertwined.” And vice versa. The same carbon emissions that imperil polar bears’ critical sea ice habitat also drown nations, whither crops, spread droughts, exacerbate wildfires, and fuel disease, among so much more. Aggressively tackling carbon emissions and reversing the impacts of climate change for humans will also directly benefit polar bears.

There’s more. While to most, polar bears are distant white-furred wonders of the far-off frozen north, they represent very real neighbors and cultural elements for many Arctic residents, especially Indigenous Peoples. The lessons in co-production and community research developing throughout the scientific community are directly applicable to pursuing mutually beneficial conservation and management for the polar bears and communities that share space in the Arctic. Engaging with the line between science and policy is similarly critical. As evidenced by Polar Bears International’s chief scientist emeritus Dr. Steven Amstrup’s recent paper Unlock the Endangered Species Act to address GHG emissions, science is needed to drive decision-making for polar bears.

But again, it’s down to you and me to make it all happen.

If you’re someone who values a safe and healthy planet where people, ecosystems, plants, and polar bears can all thrive, then I have good news for you. The message from the earth science community is clear. They have the solutions. They can say what can be done. But only we, as members of society and voters in democracies, can say what should be done. We have the power. Let’s use it.

—

Alex Shahbazi is an environmental policy, programs, & research consultant. He is an avid conservationist, writer, and advocate. Alex currently helps manage the Study of Environmental Arctic Change, an Arctic co-production research program, and assists Polar Bears International in their policy and advocacy work.