On Alaska’s North Slope, people from four Inupiaq communities—Wainwright, Barrow, Kaktovik, and Nuiqsut—cross paths with southern Beaufort Sea polar bears at various times of the year. The first three villages are perched on the coast, but Nuiqsut is located 18 miles inland, on the Colville River. Its history and patterns of interaction with polar bears are also unique.

Nuiqsut’s residents have deep roots and hunting traditions in the Colville River area, but the village itself was only formally established in the early 1970s as part of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act. The same families that resettled Nuiqsut also revived their ancestral whaling tradition on Cross Island, which is located approximately 65 miles to the northwest.

Whales and polar bears

For a few weeks each fall, whaling crews from Nuiqsut share Cross Island with the growing number of polar bears attracted to feast on the remains of whales harvested for subsistence.

The people of Nuiqsut thus have an invaluable, ongoing “snapshot” perspective on how climate change is affecting polar bears in the southern Beaufort Sea, specifically during the fall season.

In March 2018, local whaling crew members Robert Nukapigak and Steve Eric Leavitt worked with me in interviewing 13 individuals with knowledge about polar bears on Cross Island and the coastal areas to the north of Nuiqsut, which includes important denning habitat. The knowledge shared by these local experts will contribute to the ongoing project “Contemporary Inupiaq Knowledge of Polar Bears in the Southern Beaufort Sea.” This work is a joint effort between Polar Bears International, the North Slope Borough of Alaska, and the U.S. Geological Survey, and is being funded by the National Fish and Wildlife Federation and the North Pacific Research Board.

In the interviews, I took a life-history approach, focusing on each individual’s memories and knowledge of polar bears, including knowledge passed down from previous generations. Elders and younger, active whalers shared their perspectives on the physical condition of polar bears, their local abundance, seasonal movements, denning patterns, diet, and prey species—and how all of these features of polar bear ecology are being shaped by climate change. The results of the study will be published after review and approval by the participating communities.

Changing conditions

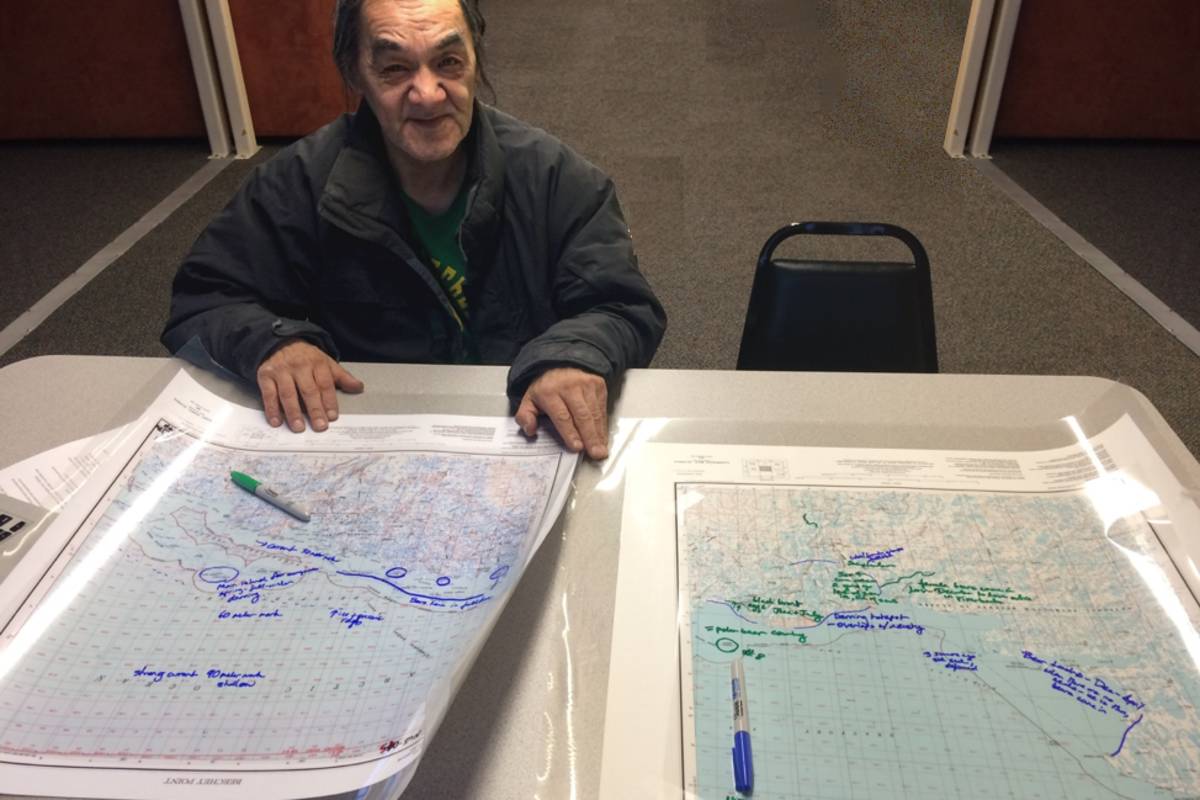

As local experts explained how the present state of polar bears on Cross Island compares with the past, I worked with Nukapigak and Leavitt to record details on topographic maps of the region. One initial observation made by many of those interviewed is that the old 1950s topographic maps commonly used for social science research no longer provide an accurate reflection of the landscape due to coastal erosion; every year, barrier islands north of Nuiqsut shift; some disappear, while new ones may appear.

With a reduced sea-ice season, these unstable barrier islands are a critical place for polar bears to gather and feed, and this means interacting with humans in an increasingly concentrated space during the few critical weeks that make up whaling season. Whaling crews have had to find new and innovative ways to manage human-bear encounters during this time; the details of these changing human-polar bear interactions will form a key element of Nuiqsut’s story in the forthcoming project report.

Lead photo caption: Whaling Captain Edward Nukapigak shares detailed knowledge of polar bear habitat use gathered over a lifetime of observation.