Polar bears rely on sea ice to reach their seal prey. Without a large-scale reduction in the use of fossil fuels, Arctic warming and its impacts will ultimately impact the polar bear’s survival.

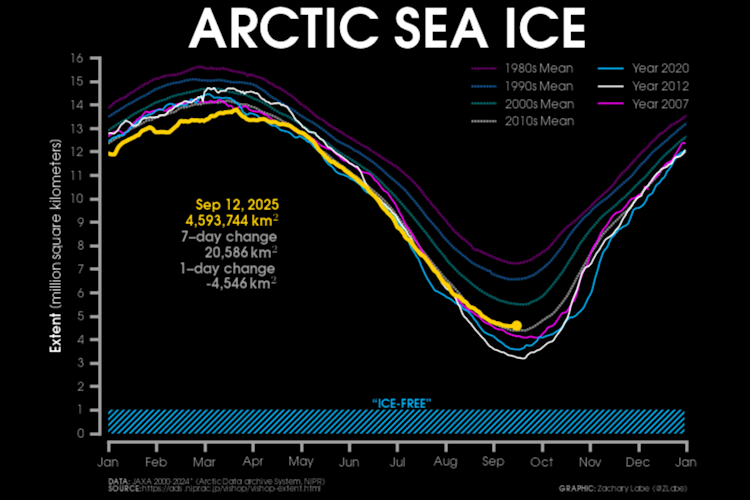

Every September our eyes turn to the Arctic for what has become a grim milestone to observe the annual minimum extent of sea ice. To no surprise, 2020 is consistent with the long-term climate trends.

This year’s Arctic sea-ice extent minimum is the 2nd lowest on record in the satellite era (since 1979). However, reconstructions of past Arctic sea ice suggest this is also the 2nd lowest extent in at least the last 1,500 years. In addition to rising temperatures (known as Arctic amplification), the total thickness and area of September Arctic sea ice has decreased by almost 50% in the last few decades. Without a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, state-of-the-art climate models continue to project the first “ice-free” Arctic summer by the mid 21st century. This will have dramatic consequences for the Arctic climate system and beyond.

Overall, this summer’s temperatures in the lower atmosphere of the Arctic were the warmest on record due to a large high-pressure system that remained in control of the weather pattern. This high pressure contributed to abundant sunshine and warmth, especially along the coast of Siberia, which led to the formation of melt ponds on top of the sea ice. In addition, a strong Arctic cyclone formed in late July across the western Arctic. This powerful storm helped to fracture and pre-condition the sea ice in the Beaufort and Chukchi Seas (north of Alaska) for further melting later in August.

As of mid-September, this year’s sea ice has retreated to the central Arctic (north of Greenland) and with a small band of older (thicker) sea ice extending out into the Beaufort Sea (Figure 1).